September 17th at the Convention

September 17th, 1787.

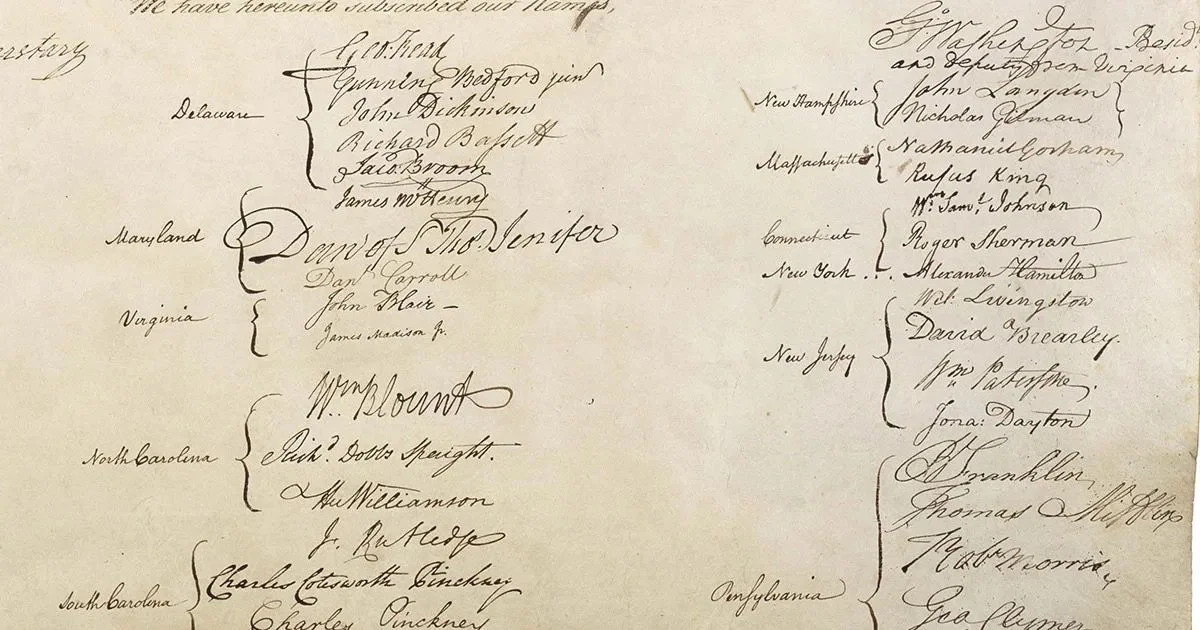

The main source we have for information on the proceedings of the Constitutional Convention, occurring in the summer of 1787, is James Madison’s notes on the convention. On September 17th, the remaining delegates (39 of the original 55, Rhode Island having refused to send delegates at all), heard the closing speeches before they prepared to vote. According to Madison’s notes, the first speech came from the pen of Benjamin Franklin, read aloud by James Wilson, and dwells upon a central point concerning the final document: no one was fully happy with it. Note how Franklin begins his speech:

I confess that there are several parts of this constitution which I do not at present approve, but I am not sure I shall never approve them: For having lived long, I have experienced many instances of being obliged by better information, or fuller consideration, to change opinions even on important subjects, which I once thought right, but found to be otherwise. It is therefore that the older I grow, the more apt I am to doubt my own judgment, and to pay more respect to the judgment of others. Most men indeed as well as most sects in Religion, think themselves in possession of all truth, and that wherever others differ from them it is so far error. Steele a Protestant in a Dedication tells the Pope, that the only difference between our Churches in their opinions of the certainty of their doctrines is, the Church of Rome is infallible and the Church of England is never in the wrong. But though many private persons think almost as highly of their own infallibility as of that of their sect, few express it so naturally as a certain french lady, who in a dispute with her sister, said "I don't know how it happens, Sister but I meet with no body but myself, that's always in the right...."He gives us no detail concerning the parts of which he disapproves, but the connection between political prudence and religious pluralism suggests that Franklin, taking him at his word, was largely motivated by a kind of humility or, more accurately, uncertainty, regarding the path to truth (in religion) or the best polity. For this reason, deference is called for:, but not only deference: Franklin draws our attention to what scholars call “the unwritten constitution,” the cultural background of habits, manners, mores, and morals that shape a people capable of self-governance. In other words, Franklin seems somewhat indifferent to the actual form of government, deferring that the actual document has its flaws, and more interested in whether “the people” could sustain republican government at all.

In these sentiments, Sir, I agree to this Constitution with all its faults, if they are such; because I think a general Government necessary for us, and there is no form of Government but what may be a blessing to the people if well administered, and believe farther that this is likely to be well administered for a course of years, and can only end in Despotism, as other forms have done before it, when the people shall become so corrupted as to need despotic Government, being incapable of any other.Independent of this “unwritten constitution,” Franklin also recognizes one of the standard tropes of political thinking: the perfect is the enemy of the good. In a sentiment Madison repeats later in The Federalist, Franklin argues that the proposed Constitution, while not perfect, is at least better than what they currently had. Furthermore, he doubts that any convention, no matter how wise the members or how much time it had available, given the difficulties of interest and compromise, would produce a better one. Here, Franklin responds to some of the document’s critics – mainly Edmund Randolph, George Mason (who, Madison reported, said “that he would sooner chop off his right hand than put it to the Constitution as it now stands), and Elbridge Gerry – all present at the Convention until the end, at which point they refused to sign. Some of the Constitution’s critics had made the argument that, given the designer’s low view of human nature, you could not expect a good system of government to emerge from vicious people, and Franklin attempts to turn that argument on its head.

I doubt too whether any other Convention we can obtain, may be able to make a better Constitution. For when you assemble a number of men to have the advantage of their joint wisdom, you inevitably assemble with those men, all their prejudices, their passions, their errors of opinion, their local interests, and their selfish views. From such an assembly can a perfect production be expected? It therefore astonishes me, Sir, to find this system approaching so near to perfection as it does; and I think it will astonish our enemies, who are waiting with confidence to hear that our councils are confounded like those of the Builders of Babel; and that our States are on the point of separation, only to meet hereafter for the purpose of cutting one another's throats.At which point Franklin offered a piece of political wisdom: sometimes it’s better to take what you can get, because of the low likelihood of ever getting anything better. Politics involves the art of settling for less than what you’d like, but more than what you have.

Thus I consent, Sir, to this Constitution because I expect no better, and because I am not sure, that it is not the best. The opinions I have had of its errors, I sacrifice to the public good. I have never whispered a syllable of them abroad. Within these walls they were born, and here they shall die.The secretiveness of the proceedings provided grist for the mills of the critics, but Franklin indicates that the silence would help build support for the final product. Constitutions, like sausage, are more palatable if you don’t know how they’re made.

If every one of us in returning to our Constituents were to report the objections he has had to it, and endeavor to gain partizans [sic] in support of them, we might prevent its being generally received, and thereby lose all the salutary effects & great advantages resulting naturally in our favor among foreign Nations as well as among ourselves, from our real or apparent unanimity. Much of the strength & efficiency of any Government in procuring and securing happiness to the people, depends, on opinion, on the general opinion of the goodness of the Government, as well as well as of the wisdom and integrity of its Governors. I hope therefore that for our own sakes as a part of the people, and for the sake of posterity, we shall act heartily and unanimously in recommending this Constitution (if approved by Congress & confirmed by the Conventions) wherever our influence may extend, and turn our future thoughts & endeavors to the means of having it well administred [sic].On the whole, Sir, I can not help expressing a wish that every member of the Convention who may still have objections to it, would with me, on this occasion doubt a little of his own infallibility, and to make manifest our unanimity, put his name to this instrument.Franklin’s speech draws our attention to an important fact about this compromise document: no one was pleased with it; some were so displeased they would not be able to support it, while other, equally displeased for different reasons, would support it because they believed it to be an essential, one might say emergency, measure.

On the negative side, speaking after Franklin’s speech, Edmund Randolph objected that he would not sign the document as he was quite sure that nine states would not vote to ratify it, and the failure of ratification would only create more confusion and discord in the fledgling nation. Likewise, Elbridge Gerry from Massachusetts “described the painful feelings of his situation, and the embarrassment under which he rose to offer any further observations on the subject.” Fully engaged in the process, he could not affirm the result. In words that sound as if they could be written today, Gerry offered the following observation:

He hoped he should not violate that respect in declaring on this occasion his fears that a Civil war may result from the present crisis of the U. S. In Massachussetts … there are two parties, one devoted to Democracy, the worst he thought of all political evils, the other as violent in the opposite extreme. From the collision of these in opposing and resisting the Constitution, confusion was greatly to be feared. He had thought it necessary, for this & other reasons that the plan should have been proposed in a more mediating shape, in order to abate the heat and opposition of parties. As it has been passed by the Convention, he was persuaded it would have a contrary effect. He could not therefore by signing the Constitution pledge himself to abide by it at all events. The proposed form made no difference with him. But if it were not otherwise apparent, the refusals to sign should never be known from him. Alluding to the remarks of Docr. Franklin, he could not he said but view them as levelled at himself and the other gentlemen who meant not to sign.Gouverneur Morris, main writer of the Preamble and who had spoken more often than anyone else at the convention, advocating for a strong executive and national government, considered the document inadequate on those terms, but nonetheless agreed to sign it. Madison:

Mr. Govr. MORRIS said that he too had objections, but considering the present plan as the best that was to be attained, he should take it with all its faults. The majority had determined in its favor and by that determination he should abide. The moment this plan goes forth all other considerations will be laid aside, and the great question will be, shall there be a national Government or not? and this must take place or a general anarchy will be the alternative. He remarked that the signing in the form proposed related only to the fact that the [FN7] States present were unanimous.Likewise, Alexander Hamilton, in many ways the document’s greatest defender, expressed his reservations about the Constitution’s final form, saying that “no man's ideas were more remote from the plan than his were known to be.” Nonetheless, he “expressed his anxiety that every member should sign,” for if anyone refused to do so it would “do infinite mischief” by attenuating enthusiasm for the proposed Constitution, resulting in “anarchy and convulsion” throughout the land.

Madison’s last entry, written while the delegates signed the documents, referred back to Franklin:

Whilst the last members were signing it Doctr. FRANKLIN looking towards the Presidents Chair, at the back of which a rising sun happened to be painted, observed to a few members near him, that Painters had found it difficult to distinguish in their art a rising from a setting sun. I have said he, often and often in the course of the Session, and the vicisitudes [sic] of my hopes and fears as to its issue, looked at that behind the President without being able to tell whether it was rising or setting: But now at length I have the happiness to know that it is a rising and not a setting Sun.Director of the Ford Leadership Forum, Gerald R. Ford Presidential Foundation

Related Essays