Whither the Refugees?

Armed conflicts around the world generate large numbers of refugees. For example, it is conservatively estimated that the number of people who have been displaced, either abroad or within their own countries, from war zones of Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia, the Philippines, Libya, and Syria is 38 million. Additional millions have been displaced by the conflicts between Ukraine and Russia and Israel and the Palestinians. And such individuals are not only displaced – in many cases, they also lack access to food and water, healthcare, employment, and education.

How to handle refugees is the subject of ongoing debate. Those against accepting international refugees generally argue that they will take American jobs and lower wages, that they represent an added burden on institutions such as schools and hospitals, and that they strain social welfare funding, contributing to state and federal budget deficits. Those in favor of accepting refugees argue that, after a period of transition, refugees contribute to the workforce and tax base, that the United States has a responsibility to assist those seeking safety from violence and persecution, and that accepting refugees simply saves lives.

US President Gerald Ford faced his own refugee crisis. At the end of the Vietnam war, with the impending fall of Saigon and the triumph of North Vietnam over US ally South Vietnam, it became clear that many South Vietnamese, Laotians, and Cambodians would face persecution, imprisonment, or even execution for their roles in assisting US war efforts. These included people who had worked as translators, who had been employed by US agencies, and who had served in the South Vietnamese armed forces. The US could no longer protect such people in their homeland.

So in the spring of 1975, Ford convened an interagency task force to determine how to handle these refugees. Those who opposed assistance argued that such individuals would never assimilate to US culture, that the cost of a resettlement program would be too high, and that funds for such a program would be better expended on helping poor Americans. In favor of aid were labor unions and religious groups. Ford himself argued strongly in favor of aid, saying “We are seeing a great human tragedy as untold numbers flee. The US has been doing and will continue to do its utmost to assist these people.”

In May of 1975, Ford signed the Indochina Migration and Refugee Assistance Act, which would provide funding for the transportation, reception, and resettlement costs of approximately 130,000 refugees who would be evacuated. Most were initially housed in Guam and then transported to centers on US military bases, including Camp Pendleton in California, Fort Chaffee in Arkansas, and Fort Indiantown Gap in Pennsylvania. Religious organizations such as the Catholic Conference, the Church World Service, and the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society also played a key role.

Another notable part of this effort came to be called “Operation Babylift.” Its purpose was to airlift orphans out of Saigon aboard American military aircraft. Over 2,500 infants were flown out. I know of a family that expected to receive one of these infants, whose name and picture they had received in advance. However, shortly after takeoff, the plane encountered severe mechanical problems and had to crash land, hitting a bridge and breaking apart, resulting in the deaths of 78 of the infants and about three-dozen personnel. Among the dead was the infant that my friends had hoped to adopt, a devastating loss.

The dangers of remaining were rumored to be greatest for children fathered by US servicemen, who could be distinguished by their appearance from those of Vietnamese fathers. One mother expressed the fear that her daughter would “be soaked with gasoline and burned.” Yet opponents condemned the airlift for poor planning and for taking children away from their own culture and community. Others found that many of the children were not orphans at all and argued that they had only been placed in orphanages because their families were having difficulty supporting them.

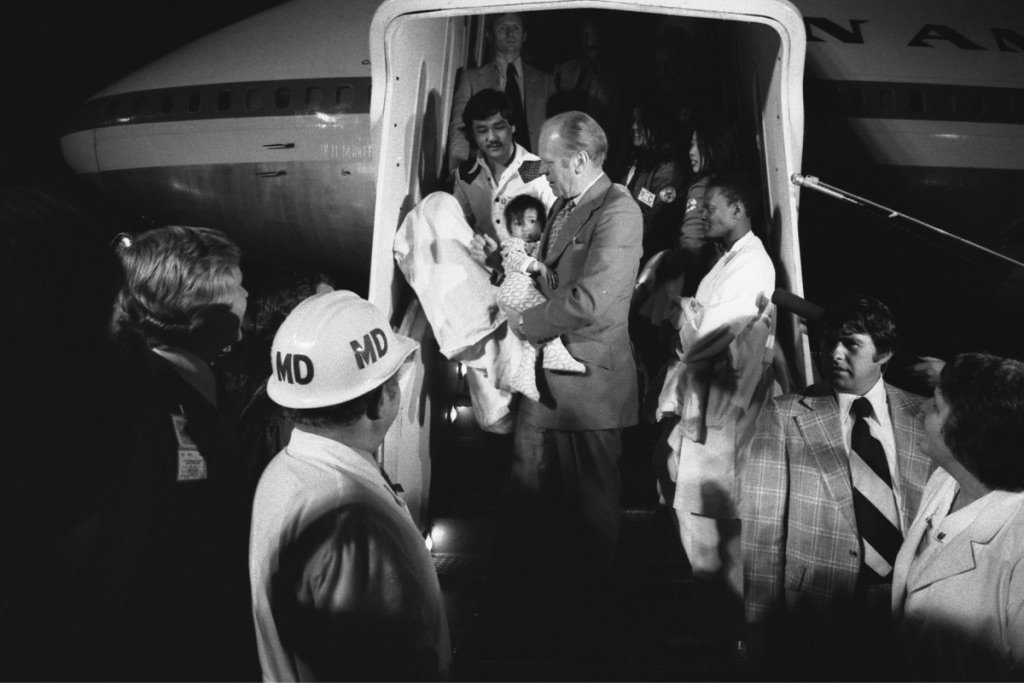

At any rate, the plight of the Vietnamese children drew support not only from government and philanthropic organizations but also from private individuals. After the crash of the first Babylift plane, US businessman Robert Macauley, a former Yale roommate of President George HW Bush, decided to take action. He chartered a Boeing 747 aircraft from Pan American World Airways and arranged for it to transport more than 300 orphans, paying for the effort in part by mortgaging his own home. When the plane landed in San Francisco, Ford was there to help carry the children off the plane.

In fact, Macauley went on to found an organization, AmeriCares, which has helped to provide funding for refugees in countries throughout the world. He served as the organization’s chief executive, drawing no pay, until 2002, distributing supplies donated by companies to people in need. Decades later, one of the infants Macauley’s airlift had rescued wrote him a note of thanks as an adult: “You gave me and my brother a life of opportunity with a loving family that were able to provide us with love, care, compassion, and support. I owe my life to you.”

Ford himself strongly supported these programs even in the face of unfavorable opinion surveys, which put public support for such a program at only 37%. With time, however, more Americans came to favor the program, and the Carter administration continued to accept large numbers of Southeast Asian refugees, an attitude that generally prevailed until US conflicts in the Middle East, when fears of terrorism took center stage. At the time, Ford was described as “damned mad” about opposition to aiding Vietnamese refugees, and he was quoted as saying:

I am primarily very upset because the United States has had a long tradition of opening its doors to immigrants of all countries. We’re a country built by immigrants from all areas of the world, and we’ve always been a very humanitarian nation, and when I read or heard the comments made a few days ago, I was disappointed and very upset. It just burns me up. [Some people] just want to turn their backs. We didn’t do it to the Hungarians, we didn’t do it to the Cubans, and damn it, we’re not going to do it now.In the echoes of the president’s indignation, we can hear the words of one of his predecessors, John Kennedy, who declared that the United States is “a nation of immigrants.” Except for those of Native American ancestry, themselves ultimately descended from prehistoric immigrants, every American either immigrated or is descended from immigrants to this land. As George Washington said, the United States was founded “to receive not only the opulent and respectable stranger, but the oppressed and persecuted of all nations and religions.” In short, assisting refugees is part of our nation’s DNA.

Richard Gunderman is Chancellor's Professor of Radiology, Pediatrics, Medical Education, Philosophy, Liberal Arts, Philanthropy, and Medical Humanities and Health Studies, as well as John A Campbell Professor of Radiology, at Indiana University.

Related Essays