McCulloch v. Maryland (1819)

Introduction

Among the pantheon of the Supreme Court’s greatest hits, McCulloch v. Maryland typically rates near the top, and deservedly so. In confronting fundamental questions around the reach of the central authority and its relation to the states, Chief Justice John Marshall’s decision in McCulloch would provide an enduring foundation for the government that was to come.

The “Necessary and Proper” Clause and the Implied Powers of Congress

A central question of the Convention was how best to address the weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation while also ensuring the new government would not be so powerful as to threaten individual liberties. The federal government was understood to be one of limited powers. Article I specified that “All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States.” Congressional authority was to be confined to those powers given it in the Constitution. The drafters dealt with the impotence of the Articles of Confederation with eighteen explicit grants of power in Article I section 8, most in response to identifiable weaknesses under the previous government.

The issue that would ultimately give rise to McCulloch v. Maryland was the “necessary and proper” clause, also called the elastic clause or the sweeping clause, which followed the list of enumerated powers and extended Congress’s authority to “make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers.” But just how far did those unnamed powers extend? That question would be hotly contested at the Convention; anti-federalists argued for a strict, tightly construed clause, one that was at its core a constraint on congressional power, restricting it to explicit delegated powers.

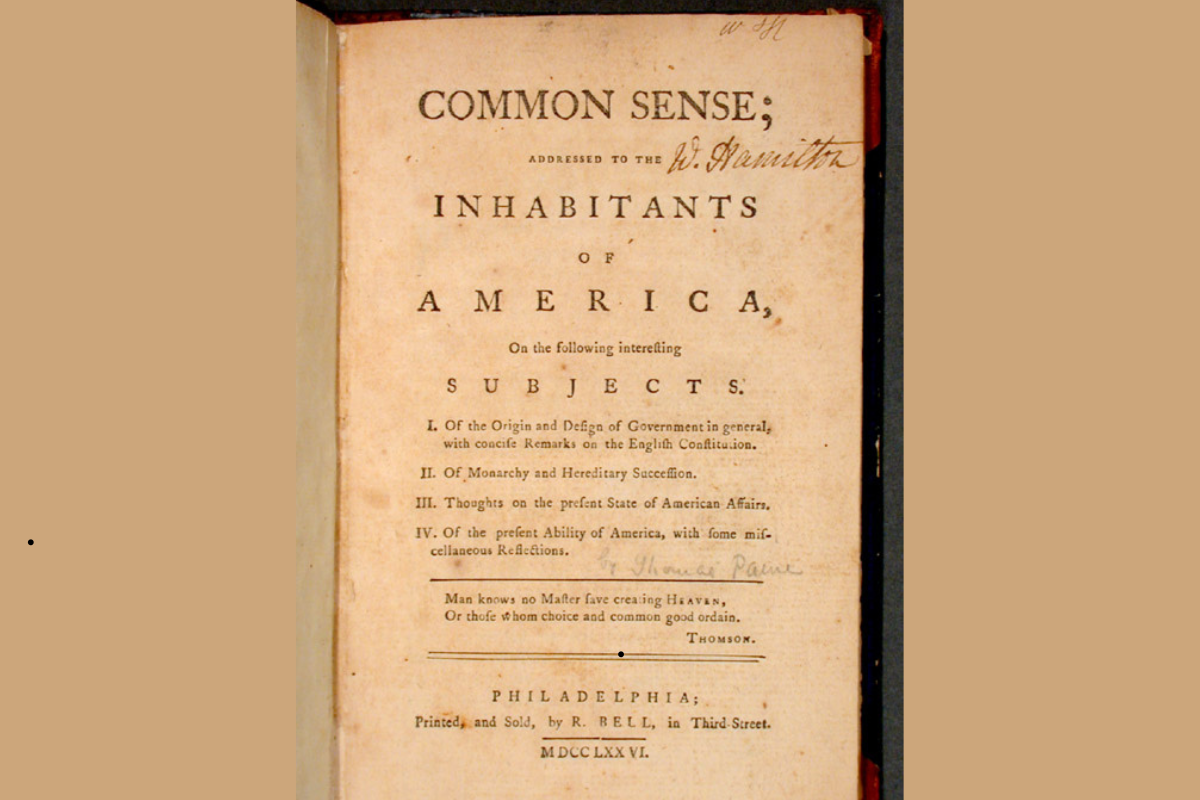

On the other hand, Hamilton and Madison were among those who argued for a broad, loosely interpreted clause that would give Congress needed latitude to pass appropriate legislation. They saw the clause at its center as a way of ensuring the central government would have ample means of carrying out its work.

Hamilton in Federalist 33 tried to ease fears that the “necessary and proper” clause would inevitably lead to “local governments . . . destroyed and their liberties exterminated.” It did not grant new powers but simply assured Congress the means of effectively executing its enumerated powers. In Federalist 44, Madison joined in the defense of the “necessary and proper” clause; without it, he worried that the “whole Constitution would be a dead letter.” He deemed it axiomatic that “wherever the end is required, the means are authorized; wherever a general power to do a thing is given, every particular power necessary for doing it, is included.” Thus did the new Constitution address the ineffectualness of the Articles of Confederation while protecting against governmental overreach.

The Debate Over the Creation of a National Bank

Ratification of the Constitution hardly ended the contestation of the meaning of the “necessary and proper” clause. The Convention debates and theoretical arguments of the Federalist papers quickly took on a practical dimension, in particular around the question of the creation of a national bank. Hamilton, now Secretary of the Treasury, was the foremost proponent of an energetic national economic program. He wasted no time in pursuing his agenda, promptly introducing a bold economic plan to Congress. Among other things, it directed Congress to charter a national financial institution that could pay off state debts, regulate national currency, and otherwise lend stability to a roiling national economy.

Despite significant opposition (including from Madison, who now contended that the creation of a bank was a sufficiently important act as to require explicit enumeration), the Federalist-dominated Congress authorized the First Bank of the United States. President Washington, uncertain of the constitutional grounding of the bank, solicited opinions of his cabinet, including Hamilton and Jefferson. Jefferson opposed the bill, endorsing a narrow construction of the word “necessary” to include only those powers essential to carrying out delegated powers, those “means without which the grant of the power would be nugatory.” The incorporation of a bank was not absolutely essential to Congress’s ability to carry out the explicit powers it had been given, and hence the bill was unconstitutional.

Hamilton countered with a broad meaning of necessary, that included “needful, requisite, incidental, useful, or conducive.” If it was “useful” for Congress to charter a bank to carry out other enumerated powers, then it had that power under the “necessary and proper” clause. Arguing that powers vested in Government must include “all the means requisite and fairly appliable to the attainment of the ends of such power,” Hamilton saw the incorporation of a bank as naturally related to such specific constitutional grants of power as “collecting taxes, to that of borrowing money, to that of regulating trade between the states, and to those of raising and maintaining fleets and armies, and hence clearly well within the provision authorizing the making of all needful rules and regulations.” He offered a test in support of his reading of the clause; “The relation between the measure and the end; between the nature of the mean employed toward the execution of a power, and the object of that power must be the criterion of constitutionality.”

Hamilton would carry the day. Washington’s reservations assuaged, he signed the bank bill into law. Authorized for twenty years, the Bank would remain a subject of controversy, closed linked with the increasingly unpopular Federalists’ more expansive views of national economic power. By the time the Bank came up for reauthorization in 1811, the Democratic Republicans had assumed control of both Congress and the presidency and refused to reauthorize the Bank. Nevertheless, the War of 1812, growing industrialization, and a host of other economic problems generated a national coalition to recreate a national bank. Ever the model of consistency in this story, (now President) James Madison switched sides once again, overseeing the chartering of the Second Bank of the U.S., which was reauthorized by Congress in 1816.

Questionable practices by the Second Bank quickly brought it into controversy. A boom of speculative investments led it to tighten fiscal policies and begin recalling outstanding loans, leading to widespread failure of overextended banks. The Bank was plagued by accusations of fraud and embezzlement, including the Maryland branch, with its main cashier James McCulloch the most seriously implicated. The state of Maryland responded with a tax on all notes of banks not chartered in Maryland, the only one of which just happened to be the Maryland chapter of the National Bank. When the state sought to collect the $15,000 fee, McCulloch refused payment, triggering a constitutional confrontation implicating both the “necessary and proper” clause and the supremacy clause.

A Foundational Interpretation of Congress’s Implied Powers: The Court Weighs In

When Maryland sued to collect its fee, McCulloch defended on grounds that the Supremacy Clause protected the bank from taxation by a state entity. Maryland in turn used the lawsuit to resurrect claims that the bank itself was unconstitutional. Thus did the case throw two major constitutional principles into question. In a unanimous decision, the Supreme Court found for McCulloch and the Bank on both issues.

Writing for the Court, Chief Justice Marshall conceded that the Constitution did not enumerate the creation of a Central Bank. Nevertheless, he found that was not dispositive of Congress’s power, employing parallel arguments in the process. First, Marshall appealed to simple logic, arguing that “the dictates of reason” compel the conclusion that government which has the right to act must be allowed to select the means of acting. Corporations are not created for no reason, but as incidental to specific powers expressly given and as a direct mode of executing them. Channeling the framers, Marshall concluded that having the important powers explicitly delegated to Congress, they could only have meant to give Congress ample means of carrying them out.

Second, he formulated a common sense textual understanding of “necessary” to mean that which was not only useful, but merely convenient. He rejected Maryland’s textual claim that “necessary” had to be strictly understood as a negative restriction on the right, that would have allowed only those means that are absolutely necessary or indispensable to carrying it out. To accept Maryland’s construction would have rendered the “proper” part of the clause extraneous. It also would have rendered many of the explicit delegations of power virtually useless. Marshall found the creation of the bank to be “a convenient, a useful, and essential instrument in the prosecution of its fiscal operations” and therefore an “appropriate mode of executing the powers of government.”

Finally, in language that would ring down through generations of Supreme Court decisions, Marshall issued a standard for delineating what implied powers would qualify as “necessary and proper.” “If the end be legitimate, let it be within the scope of the Constitution, and all means which are appropriate, which are plainly adapted to that end, which are not prohibited, but consistent with the letter and spirit of the Constitution, are Constitutional.”

Once the Court found the creation of the bank to be within Congress’s powers, Maryland’s effort to impose a fee or tax on it was easily disposed of. Declaring that “the power to tax is the power to destroy,” the Court struck down the tax as an unconstitutional interference with a federal institution, in violation of the Supremacy Clause. “If the States may tax one instrument, employed by the Government in the execution of its power . . . they may tax all the means employed by the Government to an excess which would defeat all the ends of Government. This was not intended by the American people. They did not design to make their Government dependent on the States.”

A Postscript

With respect to the Second Bank of the U.S., President Andrew Jackson, long a determined adversary, would ultimately have the final word. Jackson stirred populist anti-bank forces, making the bank a main target of his successful 1832 re-election campaign. When Congress sought to re-authorize the Bank in 1832, Jackson vetoed the bill, citing his oath to independently support and defend the Constitution. Jackson flicked aside the Supreme Court’s earlier sanction of the constitutionality of a national bank, declaring that the “opinion of the judges has no more authority over Congress than the opinion of Congress has over the judges, and on that point the President is independent of both.”

On the broader question of constitutional interpretation and federal power, however, Marshall and the McCulloch Court were the clear winners. As Marshall presciently stated, “This provision is made in a constitution, intended to endure for ages to come, and consequently, to be adapted to the various crises of human affairs.” In that objective, the Court undeniably succeeded.