The Paradox of Leadership

That one should want to be a leader is an unquestioned supposition of being born, educated, and entering the workforce at the turn of the 21st century. Young people are praised for “leadership qualities,” given “leadership scholarships,” and promoted for “leadership potential.” But rarely, if ever, do we stop to ask: “What is a leader anyway?” Most often when we speak of someone as a leader we mean someone who has power, more specifically, power over people. Leaders have the power to persuade friends, direct a company, unite an army, or divide a coalition. Leaders who we remember throughout history did these things at scale. This is the first and most common meaning of leadership. A leader in this sense has direct command over a group or the ability to sway others towards a certain end. The modern occupations of Influencer (who tells us what to wear) and Intellectual (who tells us what to think) are both leaders in the sense that they can naturally persuade others. They need no specialized skills, only raw charisma, to turn the thoughts and desires of a group towards a common goal. And this skill is not without use. At a simple level, think of a group of friends out together for the day. They may be undecided about their plans, but a leader casts a common vision for the group and solves their collective action issue. Or to heighten the stakes, a group stranded on an island may either descend into violent infighting or band together based on the type of vision a leader casts. She convinces them that they have a need of which they were not aware. Without a leader, their desires and needs may be felt but not put into common action.

When we use the term leader in a purely descriptive way, this is often what we mean. The charismatic, electric personality just makes things happen. But is there a difference between this quality of leadership and raw manipulation? In the face of a violent uprising in Rome, Cicero warned that the power of rhetoric is a skill like any other and can just as easily be turned towards fomenting the people to an unjust revolution as a just one. When we meet a charismatic individual, instead of praising his leadership qualities, instead we might say “He possesses exemplary manipulative qualities; he can get anyone to do just about anything.”

A second conception of leadership is prominent especially in professional fields. A leader in engineering possesses a certain set of technical know-how. She knows the difference between tensile and compressive stress. She has the knowledge of how a bridge should be built to span a certain distance. Quite literally, she knows how to get us from point A to point B. Similarly, every profession has a set of knowledge specific to that domain. A leader then is someone who has knowledge that the general populace does not possess. We naturally turn to these individuals when we have a technical problem or a question beyond our expertise.

This is the purest technical idea of leadership. In contrast to rhetoric, technical expertise does not require personal charisma. Although we may in hindsight attribute personal magnetism to Thomas Edison, the reason we remember him is for his technical expertise — capturing raw energy in a controllable, usable medium. Accident of time and place can vault a leader from expertise over a specific discipline to almost universal renown. For instance, during the Covid-19 pandemic, epidemiologists rose from niche practitioners to individuals who were widely sought after to answer technical questions: “How does the virus spread?” “How long will it last?” and “How can we protect ourselves?” This type of knowledge-based leadership is not limited to the scientific disciplines, but also encompasses how a prince might rule a city or a manager assemble a team. Not without reason do we associate this type of leader with the scientific age; many successful individuals over the past 400 years, from Ford to Fauci, have gained their success from their technical skills. Seeing the connection between cause and effect does take creativity and flexible thinking, but it cannot occur without an intimate knowledge of the discipline.

We increasingly rely on algorithms in our daily life to transform input A into output B. And we often think of algorithms (and their human equivalent, consultants) as neutral machines. Technical leaders lend their expertise in easing a particular problem. But their knowledge is not merely neutral. A leak publicized by the Wall Street Journal detailed how in 2019 consulting firms including McKinsey & Co. were tasked by the Saudi Arabian government to design a new mega-city in the deserts off the coast of the Red Sea. They drew up a 600-page plan to install world-class amenities and build the city of the future from scratch. From clearing the land to building infrastructure and amenities, they fulfilled their role as sought-after experts: get the Saudi government from point A to point B. Their plan, however, did have one catch — the people already living on the land. The McKinsey plan implied forcibly removing the people groups living on the land newly set aside for the dream city. These leaders had become mere tools in the hands of an autocracy! The technical methodology of the plan had been solved, but the outcome was ill-conceived, if not plain evil. In fact, the modern consulting firm, as standard procedure, accepts no responsibility for what is done with the information that it provides. Its leaders insist that they are simply technical automatons. But what are the implications for society when our leaders view their role as mere algorithms?

The first two concepts of leadership, put simply as charisma and knowledge, are at their core each a type of power, respectively power over people and power over the physical world. Power is the ability to bring about a desired effect and together these two power can bring about almost any outcome which a leader strives towards. But these outcomes can be either good or evil. Even if a leader tell himself he is doing good, his judgement may be clouded by the thoughts and desires of his heart. An outcome once fervently desired may be later bitterly regretting. Up to this point, our discussion has been purely descriptive, not distinguishing between the most altruistic plans and the darkest schemes. How can a leader tell whether his goals are harmful or beneficial, both to himself and to others?

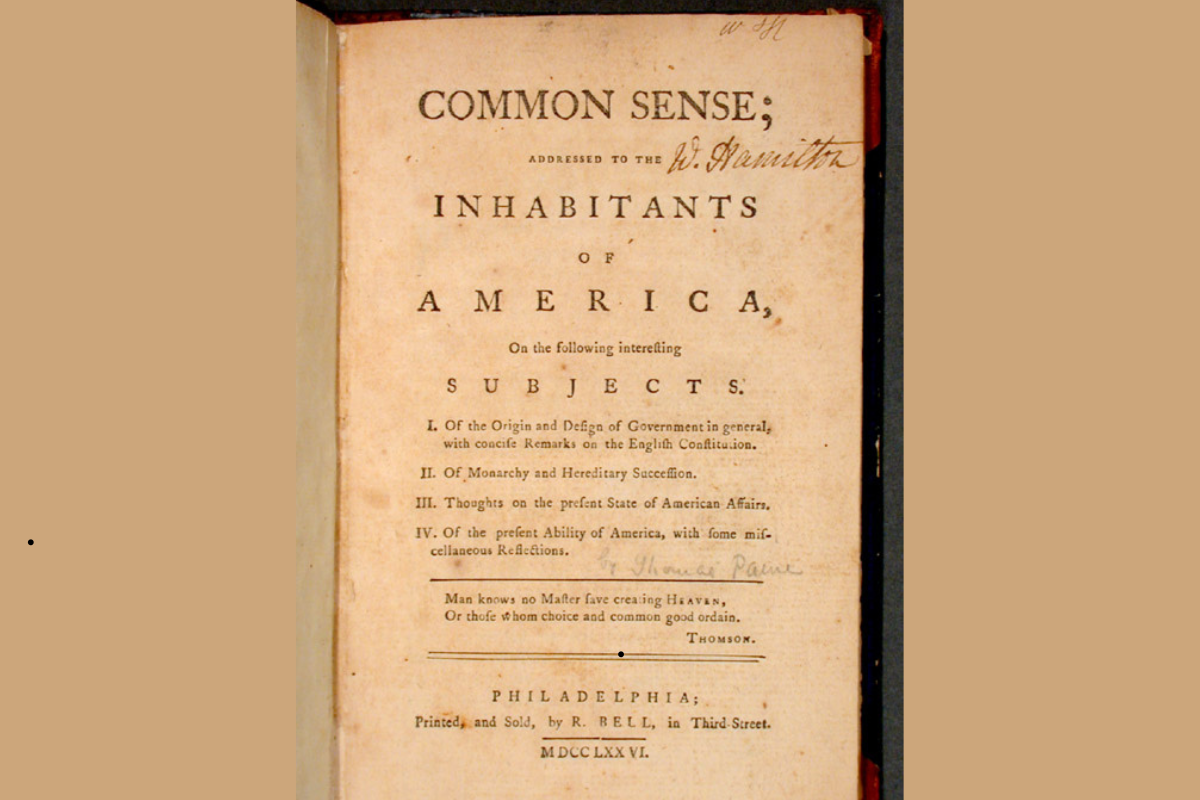

The connection between what a leader can do and what she ought to do is the paradox of leadership. A leader cultivates powers which she does not know whether or not should be employed. This paradox is certainly not limited to leadership, but mimics the paradox existent within human nature. Human freedom entails the possibility of success and peril. Humans are both intrinsically valuable, “endowed by their creator with inalienable rights,” and capable of the most horrific acts of violence and cruelty. With one hand humans build soup kitchens and hospitals while with the other they devise strange and complex new ways to kill each other. The paradox between what a leader can do and what he ought to do can create strange contradictions in his life. For instance, Abraham Lincoln’s time in office held contradictions between the lofty ideals he espoused and the pragmatic realities of the world in which he acted. The two did not always match. He grappled, as all leaders must, with the weight of his intentions and the impacts of his actions.

The leader wrestles between his dream of future reality and the double constraints of practical reality and his inner limitations of character. What he wants, what he can accomplish, and what he should do are three distinct and sometimes wholly separate realities. In addition to charisma and knowledge, a leader must add a third power, namely the power over self. This self-discipline allows a leader to constrain the greatest danger of his actions. Indeed, virtue is a type of self-discipline, an imposition of a higher order over our baser desires and appetites. This final power of leadership is certainly the most difficult. As Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn wrote, “The line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being. And who is willing to destroy a piece of his own heart?”

As we examine the lives and leadership of those who have gone before, the goal is not simple or trite answers. Instead, we must wrestle with the common conception of leadership, the ideal of leadership, and how we each fit into that picture. How can we begin to develop this knowledge of and power over self? How can we know what is good? How can we trust ourselves to protect that good over our own desires? These are the types of questions we should ask, and ultimately, they should cause us to reflect on ourselves. Leaders worthy of emulation do not allow their power of charisma or their power of intellect to outstrip their power of character. This is truly a tall challenge, but one worth pursuing nonetheless. A true leader can picture a reality not yet in place and then combine it with a knowledge of the nature of the world and the character to temper and form that dream into something truly good.