U.S. v. Wong Kim Ark (1898)

Introduction

On January 20, 2025, just hours into his second term in office, President Donald Trump signed Executive Order No. 14160, seeking to end birthright citizenship, the entitlement to citizenship of anyone born on U.S. soil. Until Trump’s order, birthright citizenship was a given, long assumed to be beyond constitutional question or challenge. The affirmation by the Supreme Court of the right grounded in the 14th Amendment Citizenship Clause dates back more than a century to the story of Wong Kim Ark. Born in San Francisco to Chinese immigrant parents, Wong successfully challenged the efforts of border officials to keep him out of this country. Amidst the roiling contemporary politics around immigration, Wong’s story bears retelling.

The 19th Century Rise of Anti-Chinese Discrimination and the First Restrictive Immigration Laws

Chinese immigrants first began to arrive in the U.S. in large numbers in the mid-19th century, in hopes of sharing in the riches of the California gold rush. Some 300,000 Chinese laborers entered the country between the end of the Civil War and 1882, seeking jobs that were plentiful in mines and railroads, farms and forests. Chinese workers played a major role in completing the transcontinental railway that would link east to west in the ever-expanding America. That was hardly enough to protect them from became targets of virulent discrimination that took the form of mob violence, property destruction, lynchings, and, eventually, legal restrictions.

The social discrimination and violence aimed at Chinese immigrants began with competition between Chinese and working-class whites for jobs. In the wake of a severe Depression in 1873, the Chinese were scapegoated for supposedly denying jobs to working-class whites. The economic resentment was amplified by widely held nativist and racist attitudes; Chinese were seen as inferiors whose differences in appearance, culture and language rendered them incapable of assimilating to broader American life. “The Chinese must go” became a common slogan among nativists in the West.

Treatment of the Chinese in the 1870s and 1880s, while far less familiar than the oppressive removal of Native Americans or the later internment of Japanese, included systematic and pervasive violence. A mob attack on Chinese in Los Angeles in 1871 resulted in the lynching of nineteen Chinese. Thirty Chinese miners were murdered in an 1885 massacre in Rock Springs, Wyoming. In countless other communities across California and the Pacific Northwest, Chinese immigrants were harassed, assaulted, forcibly expelled and their homes burned to the ground.

Rather than engendering legal efforts to protect or provide justice for the Chinese, legal action codified the discrimination in the form of the first restrictive immigration laws in America. Until the discrimination against Chinese, the U.S. essentially had open borders, its history free of restrictive immigration policies. Anti-Chinese animus changed that. For the first time in our country’s history, restrictive immigration policies took effect, aimed exclusively at Chinese migrants. Prohibitions passed by the state of California, where the largest concentrations of Chinese settled, barred them from attending public schools, testifying in court against whites, or working for any California company or in any public sector job. In other states with substantial Asian populations, “alien land laws” were commonplace, prohibiting Asian immigrants from purchasing real property.

Congress reciprocated by passing the first federal law restricting immigration involving specific ethnic groups. The Page Act of 1875 targeted Asian women under the guise of a crackdown on prostitution. The law marked the beginning of federal laws aimed at specific groups. In 1882, Congress passed the first major restrictive immigration law, the Chinese Exclusion Act, which barred most Chinese immigrants from entering the country. It was the first time the U.S. had excluded a group of immigrants based upon race or nationality. The Act required detailed registration of those of Chinese ancestry and mandated that they carry identification cards at all times. Even then, carrying proper registration did not guarantee entry into the country. Skeptical customs agents who suspected many immigrants of having false documents detained hundreds with Chinese ancestry who were trying to re-enter the country.

The Perils of Wong Kim Ark

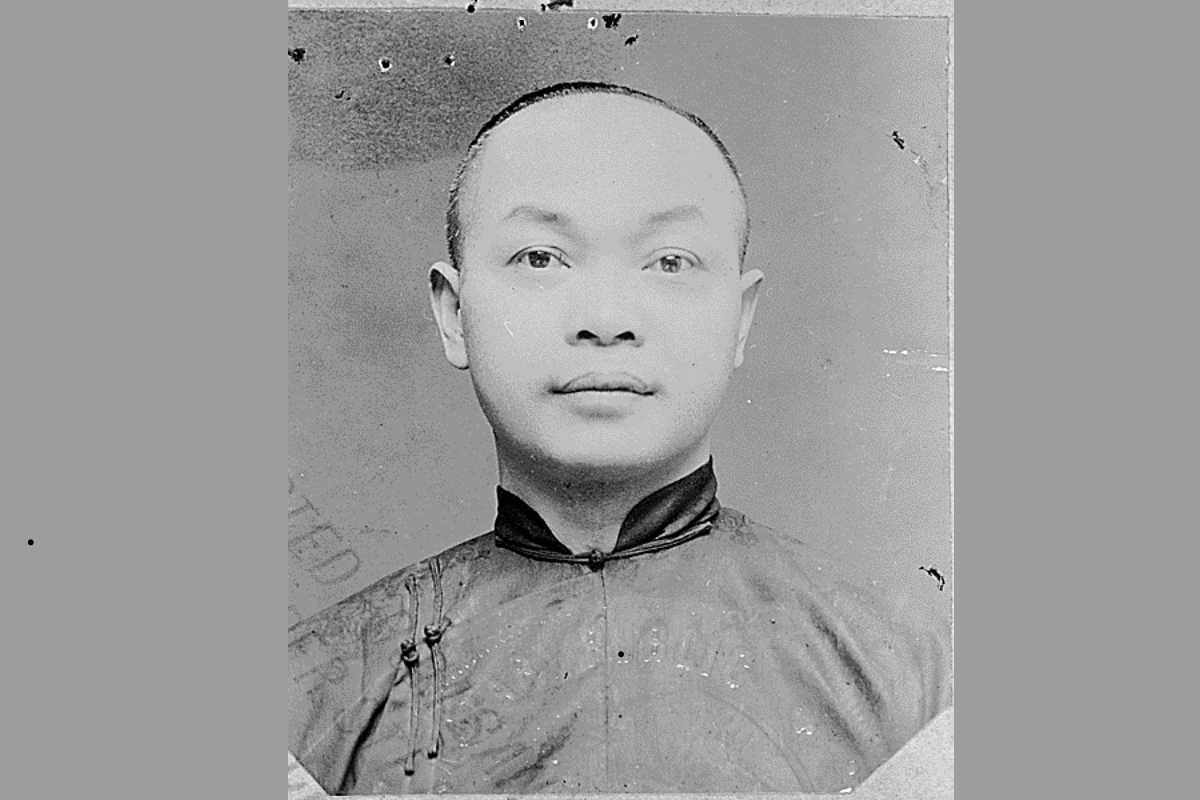

Wong Kim Ark’s back story tracks the broader developments outlined above. His parents were part of the large influx of Chinese workers seeking economic opportunities in the mid-1800s. They ended up settling in San Francisco, where Wong’s father ran a grocery story. Wong was born in 1873, and lived most of his early life in an apartment above the grocery store. The anti-Chinese discrimination may well have played a part in the decision of Wong’s family to join in the exodus of thousands of Chinese returning to China. An anti-Chinese attack by a mob of hundreds in San Francisco in 1877 resulted in the looting and destruction of countless Chinese-owned businesses, and ended with four Chinese killed. In the face of anti-Chinese discrimination and the withering of meaningful job opportunities, Wong and his family returned to their

home in Taishan, Guangdong, China.

In 1889, the sixteen-year-old Wong left his family and moved back to San Francisco, where he took on a job as a cook. By then, Congress had passed the first federal anti-immigration law, the Page Act of 1875, which would have a direct impact on the course of Wong’s life. The law barred Chinese women from entering the U.S., the practical effect of which was to make it far more difficult for Chinese men in the U.S. to find a mate to marry and with whom to start a family. It ended up necessitating their return to China in hopes of marrying.

These were the circumstances under which Wong traveled back to China in 1890. There he met and married a young woman from a nearby village. Wong returned to the U.S., but pursuant to the dictates of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, his now-pregnant wife was not permitted to accompany him. In light of the strict registration requirements for re-entry, Wong was careful to make sure his papers were in good order, with the requisite photograph and notarized statements from three whites who could attest to his identity and U.S. birth. Wong entered the country without incident. In 1894, Wong again returned to China to visit his spouse and child. This time, he was not so fortunate in his return to the States.

Wong’s Path to the Supreme Court

The Chinese Exclusion Act barred Chinese immigrants any path to citizenship. The next step for anti-Chinese forces was to attack citizenship for Chinese immigrants’ children who were born in the U.S. By the time Wong Kim Ark attempted to get back into the country in 1895, the opposition to Chinese immigration was looking for an appropriate test case that might serve as a vehicle to narrow the 14th Amendment and birthright citizenship as applied to the Chinese. Wong fit the bill. Despite having the documents that customarily ensured re-entry, Wong was stopped by an immigration officer, who challenged his citizenship status and refused him admission. He was detained on a steamer ship off the coast, and for the next six months he would bounce from ship to ship, awaiting word on his status in the country where he was born. Rather than accepting the denial of entry, Wong decided to contest the determination.

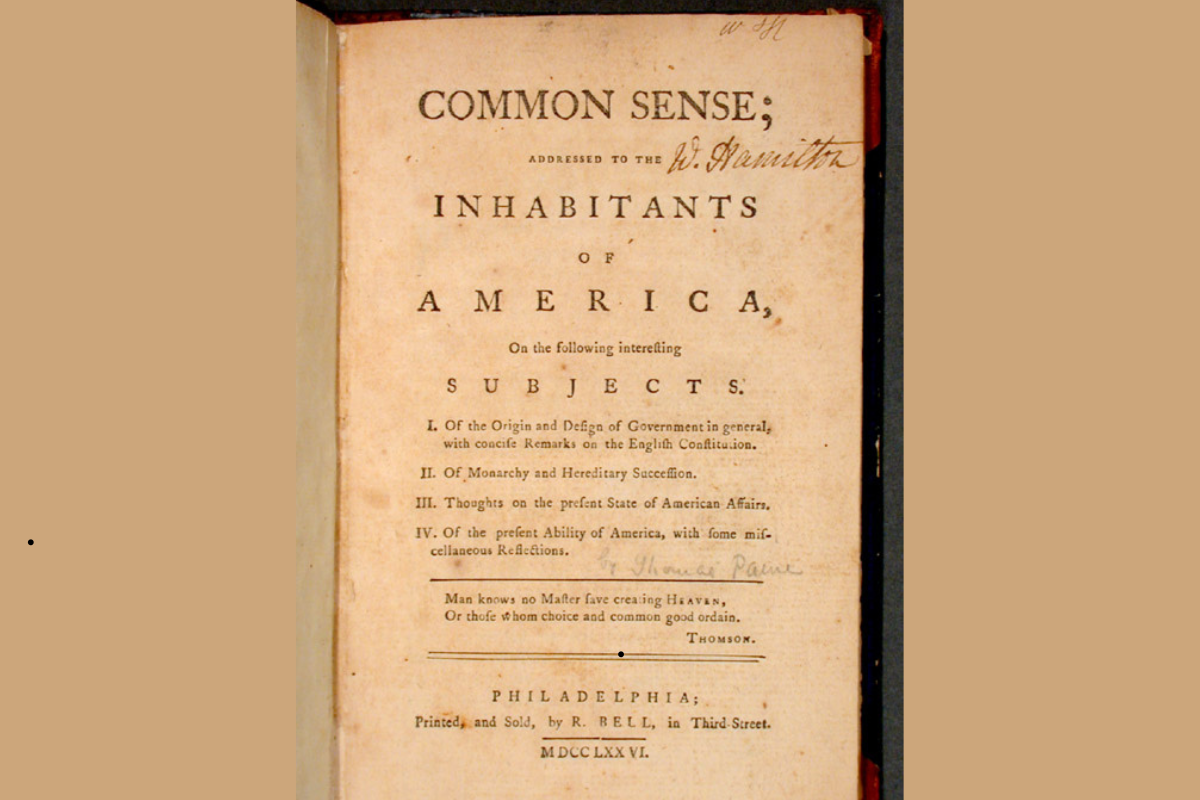

The case that ended up in federal district court in California centered on the 14th Amendment’s opening language: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United State and of the State wherein they reside.” In particular, the legal dispute hinged on whether Wong was “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” and which of the legal concepts of jus soli (“right of soil”) and jus sanguinis “right of blood”) was determinative. The principle of jus soli established citizenship as a matter of birth. Having been born in the United States automatically qualified one for U.S. citizenship. According to the tenet of jus sanguinis, citizenship was derivative of one’s parents. If born to Chinese parents, one would inherit their citizenship.

The government argued that because Wong’s parents were still citizens of China when he was born, they were subject to the jurisdiction of the Emperor of China, which rendered Wong a subject of the emperor as well. His presumed loyalty to the Emperor of China supposedly meant he was incapable of casting off his Chinese allegiances. Hence his citizenship should follow that of his parents.

The district court sided with Wong Kim Ark, declaring him to be an American citizen and ordering his release. The government responded by appealing to the U.S. Supreme Court. It would take about a year from the filing for the High Court to decide. On March 28, 1898, the Court announced its’ decision affirming the lower court decision in Wong’s favor by a 6-2 vote.

The Majority Opinion

In writing for the majority, Justice Horace Gray concluded that the 14th Amendment guarantees citizenship to anyone born in the country. Gray recognized that the “main purpose” of the amendment was to reverse the discredited Dred Scott case and to ensure citizenship for Black people, including those formerly enslaved who were born in the U.S. But the amendment by its language applied more broadly without restriction based upon “color or race.” Gray opined that the “Amendment, in clear words and in manifest intent, includes the children born, within the territory of the United States, of all other persons, of whatever race or color, domiciled within the United States.” Gray relied on what he termed an “ancient and fundamental rule of citizenship by birth within the territory, in the allegiance and under the protection of the country, including all children here born of resident aliens.” Gray noted limited exceptions for children of ambassadors and foreign consuls, and for those born to parents of invading forces, as well as children of Native Americans, who owed separate allegiance to their tribal governments at the time.

The Court also drew upon British common law notions of citizenship. Under long-standing English common law, any person born in England to a foreign national automatically became an English citizen and was judged to be “within the allegiance, the obedience, the faith or loyalty, the protection, the power, the jurisdiction” of England. At no time had U.S. courts taken issue with, or broken from, the idea of birthright citizenship under English common law.

An important undercurrent of the Court’s resolution of the issue was the possible impact on the status of the children of non-naturalized white immigrants if Wong were denied citizenship. Justice Gray remarked that “[t]o hold that the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution excludes from citizenship the children born in the United States of citizens or subject of other countries, would be to deny citizenship to thousands of persons of English, Scotch, Irish, German, or other European parentage, who have always been considered and treated as citizens of the United States.” To accept the government’s position might end up undermining the citizenship claims of hundreds of thousands of children of European immigrants from Britain German or France, and who retained some degree of loyalty to the country from whence they came. In short, the Court may have been more concerned about widespread fallout for children of European immigrants than by benevolence toward Chinese.

But whatever the Court’s underlying motivation, it laid down a simple and straightforward rule that would establish the foundation for a future America which would include all those born on its soil – Black, White, and Chinese.

The Dissenting Opinion

Chief Justice Fuller penned a dissent, joined by none other than the Great Dissenter, Justice Harlan. Fuller concluded that Wong would not be “completely subject to the jurisdiction” of the U.S., since his parents, as Chinese citizens, had a duty to the Chinese Emperor. Fuller agreed with the majority in viewing the Citizenship Clause as a response to Dred Scott; but unlike the majority, Fuller was unwilling to extend the protections of the amendment to non-citizens who he saw as owing their allegiance to another country. The 14th Amendment was aimed at former slaves and other Black persons, and was not “designed to accord citizenship” to Chinese individuals such as Wong. In light of that, the Chinese Exclusion Act was dispositive. Fuller presumed that the loyalties of one’s parents were likely to much more determinative of their allegiances than the fact of where they were born. He asserted that “[t]he true bond which connects the child with the body politic is not the matter of an inanimate piece of land but the moral relations of his parentage.”

For this reason, the circumstances of the parents were of primary importance. Fuller distinguished between those born to parents who were permanently living in the U.S. from those whose parents who “according to the will of their native government . . . are and must remain aliens.” Fuller viewed Chinese citizenship and the concomitant loyalty to the Emperor as so bound up with conceptions of duty, religious commitment, and traditions that they could not be naturalized. Hence when children born in the United States to “subjects of a foreign power . . . such children are not born so subject to the jurisdiction as to become citizens. . .”

Fuller’s disparagement of the Chinese capacity to show loyalty to the United States reflected some of the broader prejudices of the time. He characterized Chinese immigrants in the United States as having “remained pilgrims and sojourners as all their fathers were.” The dissenters went on to conclude that “[t]he place of birth produces no change in the rule that children follow the condition of their fathers . . . ‘nationality is in its essence dependent on descent.’”

Consequences

The case of U.S. v. Wong Kim Ark would become a milestone in American immigration law. Over time it would take on the status of something close to fundamental law, upheld in subsequent Supreme Court decisions and codified in federal law by Congress on several occasions. However, the decision attracted little attention when it came down, nor did it do much in the short term to improve the circumstances of Chinese immigrants still facing virulent discrimination.

Challenges to the citizenship of Chinese individuals continued well into the 20th century. So too did anti-Chinese legal policy. The National Origins Act of 1924 established a quota system with strict limits on numbers of people from specific countries who could emigrate. Those were tilted very much in favor of Western Europeans and against Asians, with immigration quotas for China at practically zero.

Long-standing immigration restrictions based upon race and nationality finally began to crumble in 1943, when repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act allowed a limited number of Chinese to immigrate. In 1952, legislation made allowance for a limited number of visas for other Asians; the law also set race aside as a basis for exclusion from America. However, the national-origins quota system persisted until 1965 and the passage of the landmark Immigration and Nationality Act. That law ended immigration policy based upon racial categorization. It replaced the system of country quotas with one that favored family reunification and skilled immigrants.

A Postscript

A positive ruling from the U.S. Supreme Court did little to simplify Wong Kim Ark’s life in the United States. In 1901, just three years after his Supreme Court victory, Wong was arrested in El Paso, Texas following a trip to Mexico. Charles Mehan, the inspector responsible for enforcing the Chinese Exclusion Act in El Paso, accused Wong of violating the statute. This time it would take about four months for Wong to convince the authorities that he was in fact a U.S. citizen and could not be deported.

Wong made another visit to China in 1905, and resumed life in San Francisco upon his return to the states. In 1910, he was joined by his eldest son, Wong Yook Fun. But Wong Yok Fun was quickly deported by immigration officials who ruled that he had failed to prove that he was Wong’s real son. He never returned to the United States.

Little is known about the remainder of Wong Kim Ark’s life. He did return to China in 1931 for one final visit. While his travel documents indicated an intent to return to the States, Wong never did.