A Half-Century After EPCA: Gerald Ford’s Battle with Congress over Energy Policy

President Gerald R. Ford faced a difficult decision. Just before Christmas 1975, Congress finally delivered an energy bill to his desk, the Energy Policy and Conservation Act [EPCA], nearly one year after Ford first proposed a program to legislators. The thrust-and-parry over energy throughout 1975 exasperated the president so much that when a reporter asked him, “What is the toughest thing that you are doing in Washington,” Ford replied that it was getting lawmakers to pass an energy program. Yet EPCA frustrated Ford, and he considered vetoing it.

The bill had commendable aspects. As one example, you may ask yourself: have you ever taken a right turn at a red traffic light? Perhaps you do every time you drive. The right-on-red traffic law was one of many measures embedded in EPCA designed to ease the “energy crisis” of the 1970s. But EPCA’s formulation remains one of history’s important clashes between a president and Congress and a milestone in public policy.

The Real Roots of the 1970s Energy Crisis

History textbooks fail to tell the full story of the 1970s energy crisis. They imply that the oil shortages and long gas station lines Americans suffered then resulted directly from the 1973-74 Arab oil embargo. True enough, in October 1973 the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries [OPEC], the powerful economic cartel formed in 1960, hit the U.S. with a crippling boycott to punish it for aiding Israel during the 1973 Yom Kippur War. Since the U.S. imported 46 percent of its oil, the cutoff created havoc with normal petroleum supplies.

But that is only part of the story. The seeds of the 1970s energy crisis were sown years earlier with misbegotten policy. In 1971, Richard Nixon’s administration imposed price controls as part of a wage and price freeze that it enacted to fight inflation. This program proved feckless and economically imprudent, especially in energy, an arena sensitive to marketplace price signals. In economics, one of the most important concepts is “incentives,” and producers rely on the incentive of higher prices to explore for and produce oil. During the 1970s, price controls distorted the oil market by discouraging oil production while encouraging consumption, allowing consumers to use more oil because its price was artificially low.

Already in 1972—more than a year before the Arab oil embargo—the country felt the hard hand of energy shortages. During the winter of 1972-73, oil shortages crimped Americans’ daily activities; some city school districts temporarily shut down to conserve fuel. Energy policy only worsened when William Simon, chair of the Nixon administration’s Oil Policy Committee, spearheaded a plan for “voluntary” oil allocations, a form of rationing that meted out supplies of crude oil and petroleum products to industries and regions. Far from helping energy supplies, voluntary allocation worsened shortages, and they paved the way for an even worse measure—mandatory allocations, which the Nixon administration introduced in October 1973 for various petroleum products. The system of price controls and allocations was a regulatory nightmare and made the U.S. vulnerable to a disruption in oil supplies.

That came with the Arab oil embargo. In response to this threat, Congress passed the Emergency Petroleum Allocation Act [EPAA], one of the most ill-advised laws in economic history. To hold down inflation, the new regulation put price controls on oil produced before 1973. The EPAA also involved a nationwide allocation scheme for crude oil and petroleum products, allotting amounts of these products to industries and regions. The result was a regulatory mess. Roy Ash, Nixon’s Budget Director, compared it to a gigantic pillow that was squeezed, creating bulges and distortions. Complaints deluged Washington about shortages in various areas, and motorists waited in long lines at gas stations—a vivid, painful scene associated with the 1970s.

The lines worsened after the Arab oil embargo. Charles DiBona, Nixon’s first energy czar and later president of the American Petroleum Institute, observed, “At no time was the shortage of gasoline—the shortage of energy in the United States—more than two or three percent. The scarcity was caused by price and allocation controls.” Gerald Ford, who had majored in economics at the University of Michigan and delved into economic issues with deep interest, knew it to be true. He later recalled that he “knew [price controls] were wrong, and we just had to find the right time to get rid of them.”

A New Energy Program

In August 1974, the Michigan economics alumnus became president, and the following January, during his State of the Union Address, Ford promulgated a new energy program, setting ambitious goals for the nation. He proposed the complete decontrol of crude oil prices on April 1, plus an array of measures including an improvement of automakers’ average fuel economy, labels on appliances to indicate their energy efficiency, and a strategic petroleum reserve (SPR) of petroleum for use during emergencies like an oil embargo. Ford believed they would cauterize America’s gaping energy wound. Business Week magazine praised Ford’s program as “the first comprehensive plan for patching and refilling the nation’s leaky oil drum.”

But on Capitol Hill, Ford’s proposals faced stiff opposition, where lawmakers worried over inflation, a problem throbbing more painfully than any other issue. Members of Congress feared that oil decontrol would trigger huge price increases. House Speaker Carl Albert, a Democrat from Oklahoma, warned that Ford’s energy plan would have “an astounding inflationary impact.”

During the summer of 1975, Ford tried to reach common cause with Congress, offering two separate compromises that involved graduate rather than immediate control. Congress rejected both olive branches. Ford’s Federal Energy Administration head, Frank G. Zarb, felt thunderstruck, recalling, “I was astounded that Congress rejected the thirty-month and thirty-nine-month decontrol [proposals]. It was so logical that they [vote for] it. It was shocking that they didn’t do it.”

EPCA: Veto or Approve?

In November, Congress hammered out EPCA, an omnibus energy bill that represented the first-ever attempt to legislate a national energy program. It was disappointing. Rather than attempt a concerted, quick effort to decontrol oil prices, EPCA swatted away Ford’s goal and instead called for more controls. It proposed rolling back oil prices and then allowing prices to rise over a forty-month period. But it gave members of Congress a political cushion, because the forty-month period of continued controls would give them cover during the 1976 election and conveniently end after the 1978 midterms.

Despite its drawbacks, EPCA had measures that Ford had requested. It proposed a strategic petroleum reserve, energy efficiency labels for home appliances, and CAFÉ standards for automakers. EPCA also had provisions for right-on-red traffic laws and energy efficiency standards for federal buildings.

In energy policy, though, Congress succumbed to the expedient of lower prices. EPCA canted toward the short term; by clinging to controls for more than three years, it would offer short-term price relief to consumers. But keeping prices artificially low would have baneful effects. Lower prices encouraged people to use more oil products, which counteracted a major imperative of the energy crisis—fuel conservation. Worse, as Frank Zarb wrote to the president, continued price controls would mean “a major reduction in incentives for investment in new, high-cost oil production.” To use economists’ standard paradigm, demand would remain high, while supply would be cut.

But in the world of Washington, politics infringed on economics. The year 1975 was almost over. After unveiling his energy proposals in January, Ford had endured political jostling with a feisty Democratic Congress, which had produced a highly imperfect bill. Yet if Ford vetoed it, the political price might be steep. 1976 was an election year, and political criticism would intensify. The blows would rain down from within his own party, too. In November 1975, former California governor Ronald Reagan announced that he would challenge Ford for the Republican presidential nomination. A veto would be unpopular in the Northeast, which depended on oil during frigid winter months, and Ford could lose the first GOP primary in New Hampshire, scheduled for February. Signing EPCA would give Ford political capital, which he needed—his approval ratings had flatlined during autumn 1974, following the adverse reaction to the Nixon pardon and the onset of a deep economic recession.

EPCA became comedic fodder. One political caricature depicted President Ford clad in child’s pajamas, sitting by a Christmas fireplace. As he held an unplugged, scrawny Mickey Mouse doll labeled “Energy Bill,” a tear rolled down the chief executive’s cheek. “Honest, Santa?” he asked. “It really took you a whole year to build this?” As an end result of Ford’s original plan for quick decontrol of oil, EPCA was indeed a cartoonish distortion. Worse, Congress had worked at a crawling pace. But the nearly yearlong effort yielded some redeeming features, like the SPR and right-on-red laws. John A. Hill, a Ford energy advisor, felt that if Ford signed EPCA into law, “we will have achieved 60-70% of a national energy program—not a bad record for the Administration or for a Congress as deeply divided as this one.”

Zarb’s opinion “was significant” in influencing his decision, Ford later remembered. The FEA chief told Ford that if he rejected the bill, Congress might send a stinging rebuke by overriding his veto. If he signed it, Zarb told the president, “we’ve got enough tools to work with to get you re-elected, and we can still get our objectives done, and there was enough in [EPCA] to do it with.” The imperfect law could act as a foundation on which to build better energy policy.

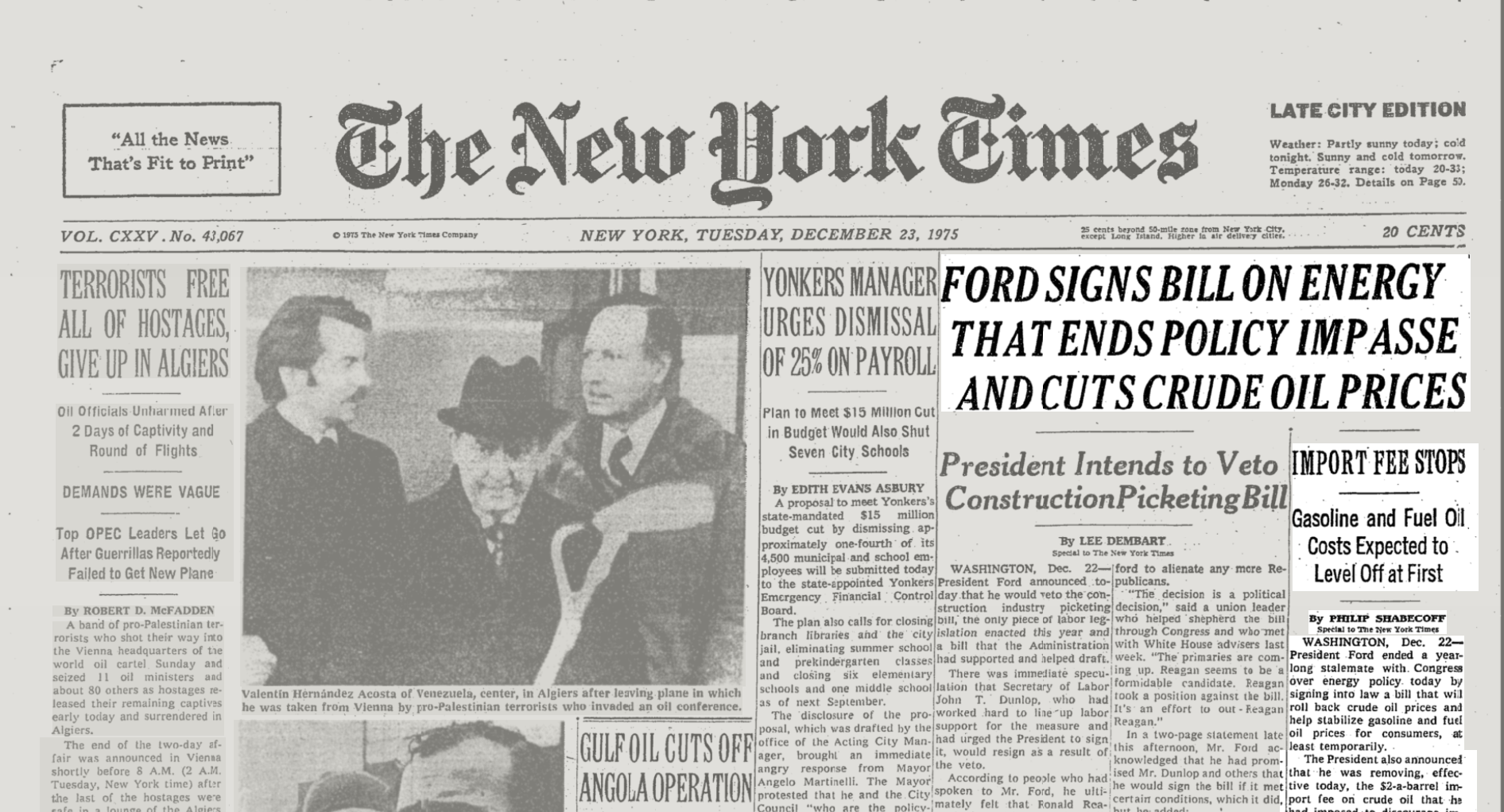

Ford felt that “half a loaf was better than none,” and on December 22, 1975, he signed EPCA into law. Nearly two decades later, he recounted how difficult the decision was, calling it “a very close call” and adding, “I signed it primarily after listening to the arguments of Frank Zarb. . . . Zarb convinced me that we had a timetable for decontrol [in the bill], we ought to accept it; there was no way we could get decontrol [immediately]. So I thought it was the best package we could get.” The president could no longer clutch at the forlorn hope that Congress would accept quick decontrol. In the end, as Ford knew, politics was the art of the possible.

In retrospect, most economists believe that complete decontrol of oil prices in 1975 would have had only a slight effect on inflation. Instead, it would have encouraged oil companies to explore for and produce more oil. With palpable pride, Ronald Reagan recounted that on January 20, 1981, immediately after being inaugurated as the 40th chief executive, “I stopped in a room in the Capitol called the President’s Room and performed my first official act as president: I signed an executive order removing price controls on oil and gasoline, my first effort to liberate the economy from excess government regulation.” That action, combined with increased OPEC production during the 1980s, helped to end the energy crisis that had dogged America in the 1970s.

“The Closest Thing to a Hero”

From the standpoint of both politics and economics, Ford was caught in a bind. Inflation loomed as a dreaded specter that it led politicians—many untutored in economics—to push for policies that were damaging, such as price controls. When Ford advocated their removal, political opponents accused him of colluding with Big Oil and warned of rampant inflation. Charles DiBona remarked that Ford “was the closest thing to a hero” in the 1970s energy crisis “because he was trying to do the right thing. And he found it impossible to do.”

Ford’s work pointed the nation toward the right solution. In mid-1975, Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield, a Democrat from Montana, credited Ford with the fillip to get legislators to act. “Because of your effort,” he wrote, “much has been done to shape and implement such a policy; more, in fact, in the past 6 months than ever before in the Nation’s history.”

Like the unsightly sausage that gets produced behind kitchen walls, EPCA emerged from hurly-burly and tussles between the White House and Capitol Hill. On different levels, it served as a metaphor for Ford’s presidency. Following the denouement of Richard Nixon’s scandal-plagued administration, Ford entered the Oval Office and tried to “heal” the nation’s political wounds, as he liked to say. Accepting EPCA—although imperfect—helped to end an ongoing impasse between the executive and legislative branches. The war on energy “was tense, and it was hot, it was nasty,” recalled John Hill. “Zarb really believed we had to end this fight. It was not healthy. And I think Ford, being a [former] member of Congress, really appreciated that argument.”

Since EPCA embraced some of his ideas, Gerald Ford helped to lay the groundwork for future energy policy. That theme encapsulated his short, 895-day presidency: Ford lacked the time in office to implement the larger policy changes he sought, but with a steady hand at the tiller, he steered the country in a better direction. “Historians generally rank Presidents by what they complete while in office,” Ford once observed. “Another way of assessing them is by what they begin.”

That was true of EPCA.

————

Yanek Mieczkowski is the author of Gerald Ford and the Challenges of the 1970s. His other books include Eisenhower’s Sputnik Moment: The Race for Space and World Prestige, The Routledge Historical Atlas of Presidential Elections, and Surviving War, Oceans Apart: Two Teenagers in Poland and Japan Destined for Life Together. Dr. Mieczkowski received his doctorate from Columbia University and teaches at the Florida Institute of Technology.