Lochner v. New York (1905)

The Lochner Slur

In his confirmation hearings to become Chief Justice, John Roberts was asked a question by Senator Orin Hatch about the difference between interpreting and making law. The question’s presumption—as was that of Hamilton’s Federalist 78—was that courts should interpret, not make law. Roberts responded to the Senator’s question by referencing Lochner v. New York (1905): “You go to a case like the Lochner case, you can read that opinion today and it’s quite clear that they’re not interpreting the law, they’re making the law. The judgment is right there. They say: We don’t think it’s too much for a baker to work whatever it was, 13 hours a day. We think the legislature made a mistake in saying they should regulate this for their health. We don’t think it hurts their health at all.” In his book The Tempting of America, Robert Bork called Lochner “the symbol, indeed the quintessence, of judicial usurpation of power.” In a rare occurrence, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg quoted Bork favorably on Lochner in her Epic Systems Corporation v. Lewis (2018) dissenting opinion. To associate a legal opinion with Lochner is to accuse its author of judicial activism and violation of the Constitution’s sacred principle, the separation of powers. What is it about the Supreme Court’s Lochner v. New York decision that is so objectionable and disconcerting?

Lochner’s reputation is also marred by what its critics charge was a heartless rejection of labor law in deference to social Darwinism and an extreme form of laissez-faire capitalism. That reputation has much to do with Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes’s dissent in the case and less to do with its historical record. Contrary to its reputation, the Lochner era is not so much about judicial lawmaking as it is about the perception that the Court was quick to reject progressive legislation intended to protect workers’ safety, health, and welfare by checking the power of industry and business. When the Court engaged in activism later in the twentieth century, not different in form from Lochner, the reaction was mixed rather than uniform.

The Tension Between Judicial Activism and Judicial Restraint

The national and state constitutions empower their respective legislatures to create laws. Law-making power, however, is not absolute. The creation of laws must abide by processes that are themselves the product of law, including due process of law. For example, under the national Constitution, revenue bills must originate in the House of Representatives, and all federal laws must pass through both houses of Congress in the same exact language by at least a simple majority vote. State and federal courts serve as a check on legislatures to ensure that legally mandated processes are followed. Disputes deriving from non-compliance with legally mandated processes are rare and relatively easy for judges to adjudicate. Determining the constitutionality of the substance of law is far more difficult because it requires judges to decide if the law in question violates constitutional clauses such as the General Welfare Clause, the Due Process Clauses, the Contract Clause, the Commerce Clause, or the Equal Protection Clause. In embracing substantive due process review of state laws, Lochner and similar preceding cases expanded judicial power and set the tone for twentieth-century judicial politics.

Some Supreme Court Justices believe that the starting point for determining the constitutionality of laws is to give the legislatures that created them the benefit of the doubt and presume that they are consistent with the Constitution. Unlike federal judges, legislators are elected to make laws and policies that promote the public good. It is not the role of judges to question the prudence or wisdom of laws but to ensure that they were created following the mandated procedures and do not violate the Constitution’s limits on the substance of law. Judicial restraint means that judges should not overturn democratically created laws unless they clearly violate required process or substantive limits on legislative power. Refraining from ideological or political judgment requires an extraordinary degree of self-restraint, perhaps more than most judges possess.

In short, Lochner v. New York is considered by some to be a classic example of judicial overreach, an egregious case of judicial activism that defined the era of substantive due process. In the early development of laws protecting workers’ health and safety, the Supreme Court struck down part of a New York statute, the Bakeshop Act (1895), that limited the number of hours that bakers could work in a day to ten and in a week to sixty. State governments were presumed to possess police powers used to promote the health, safety, welfare, and morals of citizens. What was in question in Lochner were the limits of police powers.

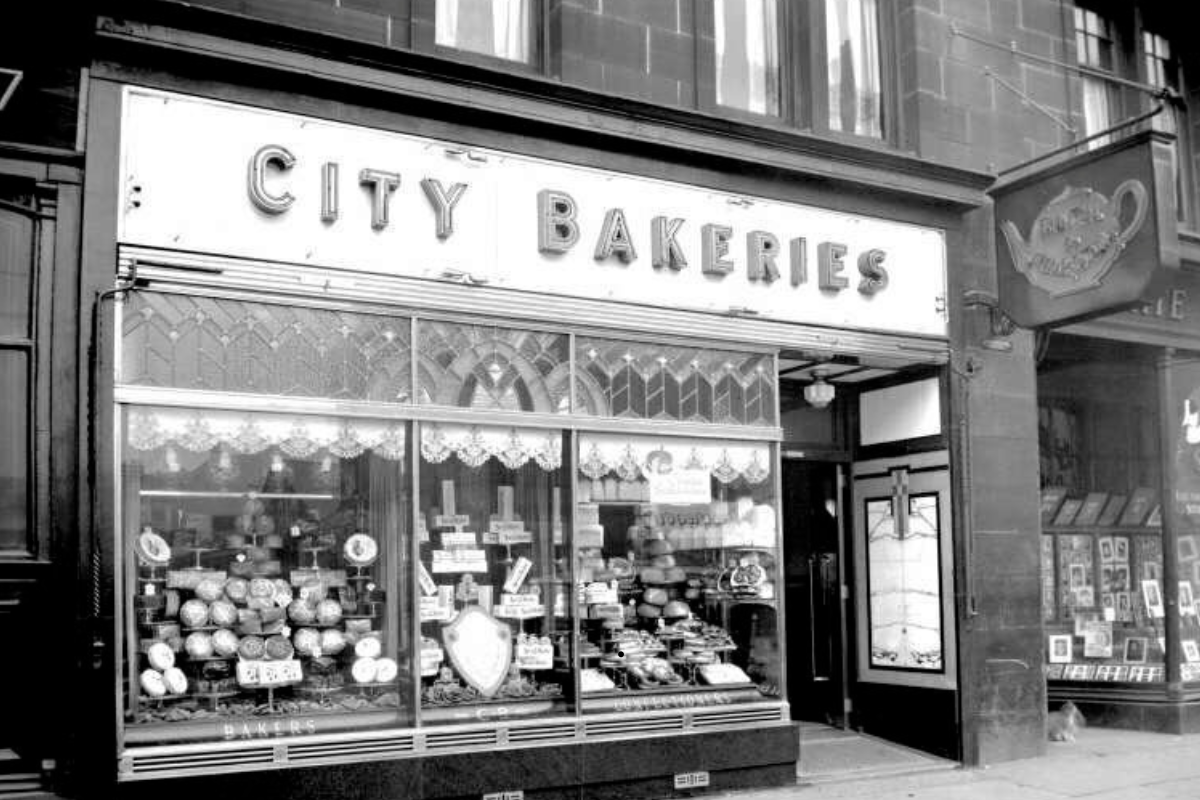

The Purpose of the Bakeshop Act

The New York Legislature passed the Bakeshop Act unanimously in an effort to protect bakers from unhealthy working conditions. Most of the law addressed specific sources of unhealthy and unsafe working conditions. In the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century, bakeshops were typically found in the basements of tenement buildings, although that was not the case with Joseph Lochner’s bakery. They were poorly ventilated, unsanitary, infested with roaches and rodents, cramped, and excessively hot. Many bakers worked twelve to fourteen hours a day, six or seven days a week. They complained of respiratory illnesses they believed were caused by their working conditions, especially exposure to flour and coal dust. The Bakeshop Act was an attempt to reduce bakers’ exposure to harmful conditions and to create more leisure time for family life.

Efforts to improve the working conditions of bakers and other workers were met with resistance. Advocates of social Darwinism or some variation of unbridled capitalism insisted that market forces would mitigate most disputes between business and labor. If particular professions were unhealthy or especially dangerous, fewer workers would be willing to enter those professions, and employers would have to improve working conditions and pay higher wages to attract workers into those professions. Government interference on behalf of workers would distort the natural forces of the market and result in economic inefficiencies and lower levels of production and wealth. Moreover, it would limit both employers’ and employees’ liberty to determine and act according to their self-interest. Some degree of legal protection for workers was necessary, especially in the case of women and children, but it was considered best to let workers decide if a particular profession was too dangerous or unhealthy.

The Legal Issues in Lochner v. New York

Joseph Lochner was a small bake shop owner in Utica, New York. In 1902 he was fined $50 for allowing an employee to work more than sixty hours in a week. It is noteworthy that the law’s limitation on hours worked applied to employees and not bakeshop owners who labored in their own facilities or bakers who were not employed in bakeshops.

Prior to Lochner v. New York, the Supreme Court upheld many labor laws. The Court’s case law, however, was mixed. In some instances, it upheld state laws that protected worker health and safety and in other instances it struck them down. The dividing line that separated constitutional and unconstitutional laws was a moving target. As is typically the case with new areas of law, courts take time to determine the boundaries of government power and the liberty of citizens. The Supreme Court was not averse to upholding certain types of labor laws, especially those that were intended to bolster morality, protect women and children, and protect workers from dangerous professions. It was less inclined to uphold laws that were thought to limit the freedom of employers and workers to negotiate contracts that was an extension of property rights protected by the due process clauses of the Constitution.

The Court’s Ruling in Lochner v. New York

In a 5-4 ruling the Supreme Court struck down section 110 of the Bakeshop Act that placed limits on the hours that bakers could work. It left in place the law’s provisions regulating ventilation, flooring requirements, ceiling heights, pipes, wash-rooms, drainage, painting, and other aspects of bakers’ working conditions. The majority separated these requirements from the working hours provisions. Once the sources of unhealthy working conditions were eliminated, the question of working hours appeared in a different light. In other words, it was possible that long working hours were not the cause of bakers’ health problems.

Justice Peckham wrote for the Court. He framed the legal dispute as a matter of freedom to negotiate contracts. An “absolute prohibition” limiting workers to ten-hour days and sixty-hour weeks violates the liberty of contract protected by the Fourteenth Amendment Due Process Clause and identified in Justice Peckham’s majority opinion in Allgeyer v. Louisiana (1897). The liberty of contract is not absolute. It is balanced by states’ police powers to protect the “safety, health, morals, and general welfare of the public.” States can prohibit particular kinds of contracts. For example, contracts that promote immorality or unlawful activity can be prohibited. So too, police powers are not absolute. States cannot limit the freedom of individuals “without foundation.” The limitation of liberty must be justified by some public good. In this instance, the law does not promote a public good. “Clean and wholesome bread does not depend upon whether the baker works but ten hours per day or only sixty hours a week.” Implicit in Peckham’s argument is that eliminating the sources of unhealthy and unsanitary working conditions was conducive to the public good and did contribute to the production of wholesome bread. Reducing the number of hours that bakers worked, however, did not have the same effect. Moreover, he argued that the baking profession “is not an unhealthy one to that degree which would authorize the legislature to interfere with the right to labor.” The baking trade is healthier than some professions and unhealthier than others.

Dissenting Voices

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes accused the majority of reading the Constitution through the ideological prism of social Darwinism. He listed several Supreme Court decisions that, he believed, contradicted the majority’s ruling because they upheld state laws limiting business. He emphasized a point that he would repeat in his dissent in Gitlow v. New York (1925): political and popular majorities should have their way. In his Lochner dissent, he qualified this plea for majoritarianism by suggesting that courts can legitimately check legislatures if a “rational and fair man necessarily would admit that the statute proposed would infringe fundamental principles as they have been understood by the traditions of our people and our law.” A similar rationality has been used more recently in cases like Washington v. Glucksberg (1997), a right to die case, and Dobbs v. Jackson (2022), the abortion decision that overturned Roe v. Wade that was also based on Holmesian logic.

Justice John Marshall Harlan refuted the majority’s claim that the baking profession was not so unhealthy as to justify legislation limiting working hours. He cited a study that supported the idea that the baking trade was particularly unhealthy. He did not reject the existence of a liberty of contract under the Fourteenth Amendment but argued that legislatures can limit it if justified by “the common good and well-being of society.” While Justice Harlan provided evidence that the baking profession was harmful, he insisted that it was not for the Court to decide such matters. The prudence and efficacy of law is the prerogative of legislatures, not courts.

Lochner’s Legacy

Lochner’s legacy is somewhat misunderstood. While the Lochner Court is open to the charge that it engaged in judicial activism, it stretches the ruling’s meaning to suggest that it was simply a case of heartless social Darwinists refusing to allow a state legislature to remedy the working conditions of bakers. Such a view is a caricature. The Court refrained from disturbing any of the health, safety, and welfare provisions of the law. It only struck down section 110 that restricted working hours. In fact, from 1889-1918 the Supreme Court upheld the exercise of state police powers 87% of the time. Justice Holmes’s remarks that the “case is decided upon an economic theory which a large part of the country does not entertain” and the “14th Amendment does not enact Mr. Herbert Spencer’s Social Statics,” have made a greater impression than anything in Justice Peckham’s majority opinion. Intentionally or not, Holmes exaggerated to great effect the influence of social Darwinism on the Court’s ruling. The legacy of the case is a reminder that over time a dissenting opinion can overshadow a majority opinion, and that few people take the time to read Supreme Court opinions. Often ignored is the fact that the limitation of hours in the Bakeshop Act did not apply to bakeshop owners or bakers who were employed by restaurants and other establishments. In other words, it did not treat all bakers equally. Lochner v. New York was overturned by West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish (1937).

Professor of Political Science at Middle Tennessee State University

Related Essays