Veterans and Congressmen: Gerald R. Ford and Charles B. Rangel

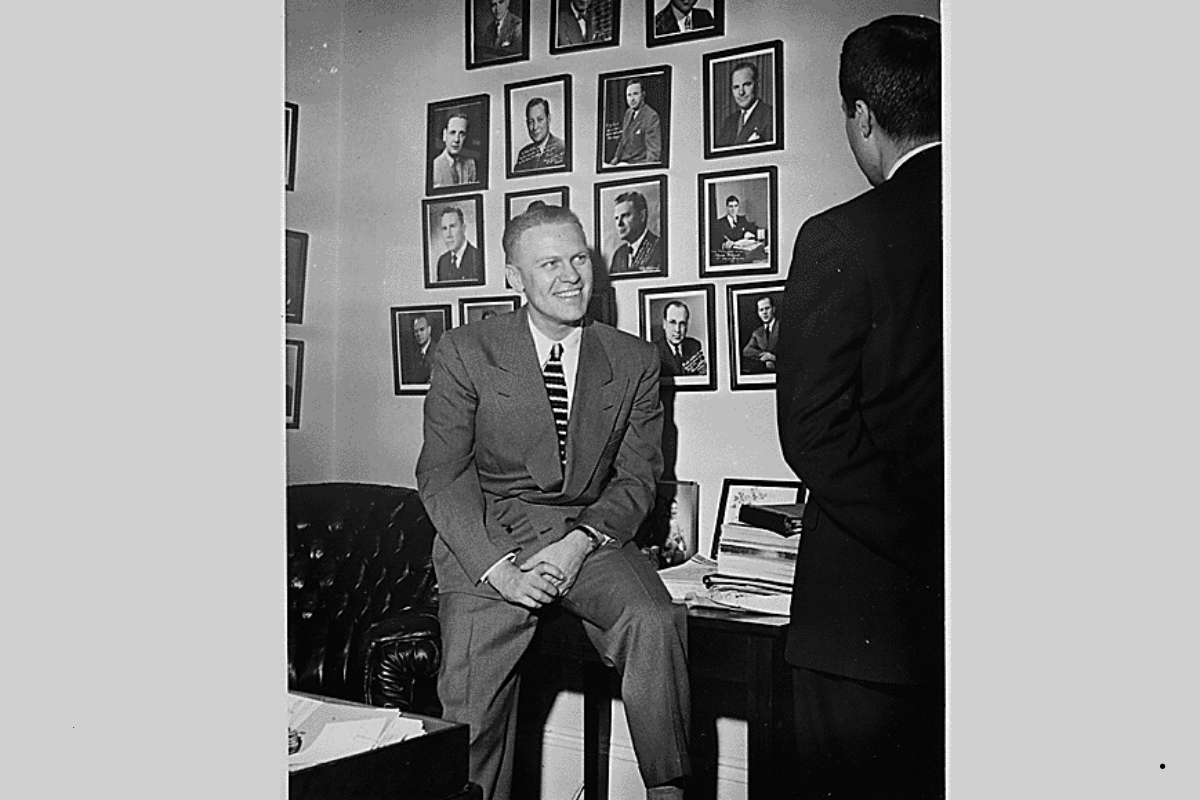

Charles Rangel and Gerald Ford were veterans of the Korean War and World War II, respectively. When Rangel was elected to Congress in 1971, history brought him together with then-Michigan Rep. Jerry Ford, first elected to Congress in 1948.

Political differences did not stop them from working together. The politically tense times of the 1970s produced leaders who successfully managed historic challenges, helping to heal a nation in need.

President Ford, in “A Time to Heal: The Autobiography of Gerald Ford,” recalled a 1974 telephone call he made to New York Representative Charles Rangel, a Purple Heart recipient in the Korean War, who died on Memorial Day 2025. Shortly after becoming President, Ford called Rangel, founder of the Congressional Black Caucus.

President Ford invited Rangel and his CBC members to the Oval Office. Rangel described the meeting as “absolutely, fantastically good.” It was an improvement in their political relationship.

In 1973, Rangel served on the House Judiciary Committee that considered Ford’s vice-presidential nomination. The Watergate scandal dominated the news. Vice President Spiro Agnew resigned in October 1973. Democrats controlled both houses of Congress. Times were politically tense and tough in the fourth quarter of 1973.

In 1994’s “Time and Chance: Gerald Ford’s Appointment with History,” James Cannon wrote that Rep. Charles Rangel was one of “the most vociferous proponents of impeaching [President Richard] Nixon.” Rangel, the author wrote, was among the “most passionate advocates of delaying the confirmation [of Rep. Ford] as vice president.”

When Democrats failed to find any scandals or political skeletons in Ford’s background investigation, the Committee recommended his confirmation as vice president.

In “Gerald R. Ford: An Honorable Life,” also by James Cannon, Rangel is described as a House opponent to Ford’s vice-presidential nomination. The author wrote that during Ford’s confirmation hearings, Rangel “looked directly at Ford and said: ‘The FBI reports … run like a testimonial to the way you have conducted yourself.”

Despite the kind words, Rangel was among the 34 House Democrats who voted against Ford’s confirmation. Rep. John Moakley, an Independent from Massachusetts, also voted against the confirmation.

J.F. terHorst in “Gerald Ford and the Future of the Presidency,” published in 1974, attributes a clever quote to Rangel, one of twenty-one Democrats on the House Judiciary Committee that considered Ford’s nomination. Rangel was “concerned about Ford’s fitness to serve as vice president, terHorst wrote.

Rangel took a special interest in Ford as he would sit “one heartbeat away or one impeachment away from the Presidency,” terHorst wrote. Again, the times were politically tense and tough in the final months of 1973.

In “Ambition, Pragmatism, and Party: A Political Biography of Gerald R. Ford,” Scott Kaufman wrote about a 1974 incident at a high school in Boston, Massachusetts, where a Black student stabbed a White student.

The tense situation led Rep. Rangel to urge President Ford to send the National Guard to the school. In 1957, President Eisenhower deployed National Guard troops to ensure the safety of students at Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, as the school underwent integration.

Ford, while serving in Congress, opposed busing as a means to enforce school integration. He preferred that state and local governments comply with federal legislation to implement plans for school integration. President Ford held firm to his position. The president did not order troops to Boston.

Kaufman wrote of another time where Ford and Rangel worked together to reduce Turkey’s cultivation of opium poppies, used to make heroin. Rangel argued that heroin was a cause of suffering to constituents in his Harlem Congressional district.

This was a complex negotiation between the U.S. and Turkey. In 1975, Turkey, a NATO member since 1952, was at war with Greece over Cyprus. The House of Representatives voted to embargo military aid to Turkey. In response, Turkey ordered Ford to stop operating U.S. military bases in the country. The bases were used to gather intelligence on the Soviet Union.

Ford supported a Senate bill to restore military aid to Ankara. Rangel offered the support of the Congressional Black Caucus for the bill if it could reduce poppy cultivation. The embargo was partly lifted with Turkey agreeing to “prevent the diversion of opium into illegal channels.” This complex negotiation represented an improvement in relations between President Ford and Rep. Rangel.

In “An Ordinary Man: The Surprising Life and Historic Presidency of Gerald Ford,” Richard Norton Smith also wrote about the complexity of the Turkish arms embargo and the Ford-Rangel connection. Norton Smith described the negotiations between the U.S. and Turkey and between Ford and Congress as a “cliffhanger.” It took President Ford several months to resolve the matter.

“[B]oth men underestimated ... the ability of embargo supporters to run out the clock,” Norton Smith wrote. “As a result, it wasn’t until the first week of October [1975] that Rangel and Ford could execute their deal and the House voted to release almost $200 million in Turkish armaments already in the pipeline.

In his 2007 memoir “And I Haven’t Had a Bad Day Since,” Rangel did not mention his opposition to Ford’s confirmation as vice president. He wrote about his friends among “Republican financial backers” who supported him when he challenged longtime incumbent Harlem Congressional Rep. Adam Clayton Powell in 1970. Those friends included then-New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller. Rangel wrote that when Rockefeller accepted the vice presidency in the Ford administration, it “was definitely a step down in power.”

Recalling the “crazy summer of 1974,” Rangel wrote: “Gerald Ford stepped into the White House following Nixon’s resignation, and he nominated my friend Governor Rockefeller to be his vice president.”

“In 1974 I gave Nixon hell,” Rangel wrote, “was courted and consulted by President Ford, and helped my Republican friend Nelson Rockefeller get as close as he ever would to his dream of being in the White House.”

On December 19, 1974, the House of Representatives voted 287-128 to confirm Rockefeller as Vice President. Rangel was among the 134 House Democrats who voted to confirm Rockefeller.

On December 20, 1974, Rangel, quoted by the Associated Press, gave Rockefeller faint praise for a “friend.” The AP reported that Rangel said House Democrats voted for Rockefeller “partly because they knew he had the experience for the job, and they weren’t sure who might get it if they rejected him.”

In 1974, publicly, Rangel kept his political distance from his “friend” Rockefeller. In 2007, Rangel opened up about “helping” his Republican “friend.” Time helped Rangel clarify his thoughts about his vote for Rockefeller’s confirmation.

Ford and Rangel were military veterans who fought political battles. At times, they were at odds with each other. Other times, they worked together. It is a testament to their leadership that they respected one another, their work, and their country.