A Republic, If You Can Keep It

Last year I decided to fix our deck. It’s big, about 600 square feet, nine feet off the ground, and it was falling apart. Joists were rotting, and the whole thing was resting on one beam, when there should’ve been three. My foot went through the floor a couple of times. Somehow, this thing passed inspection when we bought it a few years ago. So I rebuilt it, from the ground up. New beams, new joists, new decking, new railing, new stairs.

It looks great and no longer sways when you walk on it. I was feeling pretty pleased with myself. Most academics are incompetent, and for a long time I thought I was too. But I’ve lately been tapping into my farm-boy roots, and apparently it’s true that you can “just do things,” as the kids say, especially if you grew up just doing things. The deck was my grandest project yet. Real men with real skills would see it and pay me the serious compliment of not criticizing it. I felt like I’d joined a club.

But last month I got a letter from the city. It had come to their attention that my work had not exactly been authorized. The letter didn’t explain exactly how it had come to their attention, but my wife remembered that a few months earlier, two nice little old ladies had come to the door asking if they could take a few pictures. She thought nothing of it, assuming it was for property taxes or something, said ok, and went back to stopping the kids from “just doing things” of a more destructive variety. Since then, we’ve heard tell of the disarming duo from other homeowners. This, it seems, is their whole job.

It honestly hadn’t occurred to me that I’d need permission to fix something I owned, especially when what I owned had already been given permission to exist in its comically dilapidated state, and my intervention had so obviously improved the situation. I was naive, of course; people with more experience at “just doing things” know that in cities you need official permission to do pretty much anything. You can try the “ask forgiveness, not permission” approach, but forgiveness is costly and obnoxious. I will spare you the details of the process that now embroils me.

Sometimes it feels like the world is divided between people who’s job is to do things, and people who’s job is to stop things from getting done. Our political landscape often seems to be configured around this divide. Think of the tension between “entrepreneurs” and “regulators,” and how the Republicans have traditionally been the party of the former, while the Democrats have usually sided with the latter.

It’s certainly more complicated than our two-party stories suggest. The maverick entrepreneur who “moves fast and breaks things” at the start-up phase eventually builds the billion-dollar corporation stuffed with middle managers and HR “professionals” whose profession is to make sure everybody has a permission slip before they visit the bathroom. Then he hires a bunch of lobbyists whose profession is not to eliminate old regulations but to eliminate upstart competitors by persuading (paying) politicians to create new regulations so arcane that only corporations big enough to have an HR department can comply with them. Now the entrepreneur is a rent-seeking monopolist. His job is no longer to do things, but to stop other people from doing things better or more cheaply than he can. Once this happens, real entrepreneurs need unlobbied regulators to stop the “entrepreneurs” from stopping the real entrepreneurs from making new things happen, and the real, unlobbied regulator is a friend of the people who “just do things,” while the people who have done things that make them “too big to fail” become a friend of the “regulators” who’ve been properly lobbied.

So the “party of the free market” versus “the party of government” framing has always obscured more than it clarifies. Still, I think there’s something useful about the idea of “people who do things” versus “people who stop things from being done.” It points to a more fundamental political question that predates our contemporary political categories. What’s really at stake here is our understanding of “freedom.”

There’s a difference between prohibiting something, on the one hand, and requiring permission for it, on the other. The traditional American notion of freedom is bound up with the idea you are free to act unless the law says otherwise. Being “free” doesn’t mean that you can do whatever you want, since the law does prohibit you from doing certain things. But it does mean that if something is not prohibited by law, you don’t need permission to do it. When you need permission to do something, you’re not really free to do it, even if permission is always granted. At school, you’re not exactly prohibited from using the restroom during class, but you do need permission before you go. While you’re at school, you lack freedom in the traditional American sense of the word.

We’re used to thinking of the United States as a “liberal democracy.” Often we take it for granted that the two terms are a natural pair. If we’re thoughtful, we focus on the tensions between them. But the original American notion of freedom is neither liberal nor democratic. Democracy imposes the will of the majority on the minority, and the majority may decide that the minority needs permission to go out after curfew (purely hypothetical, of course). Liberalism protects the rights of the minority, whether that’s the individual (classical liberalism) or the group (progressive liberalism), against the majority’s depredations. Lately, this seems to involve making sure everybody is properly credentialed before they interact with each other; the apotheosis of liberalism is the idea of “parental licensing.”

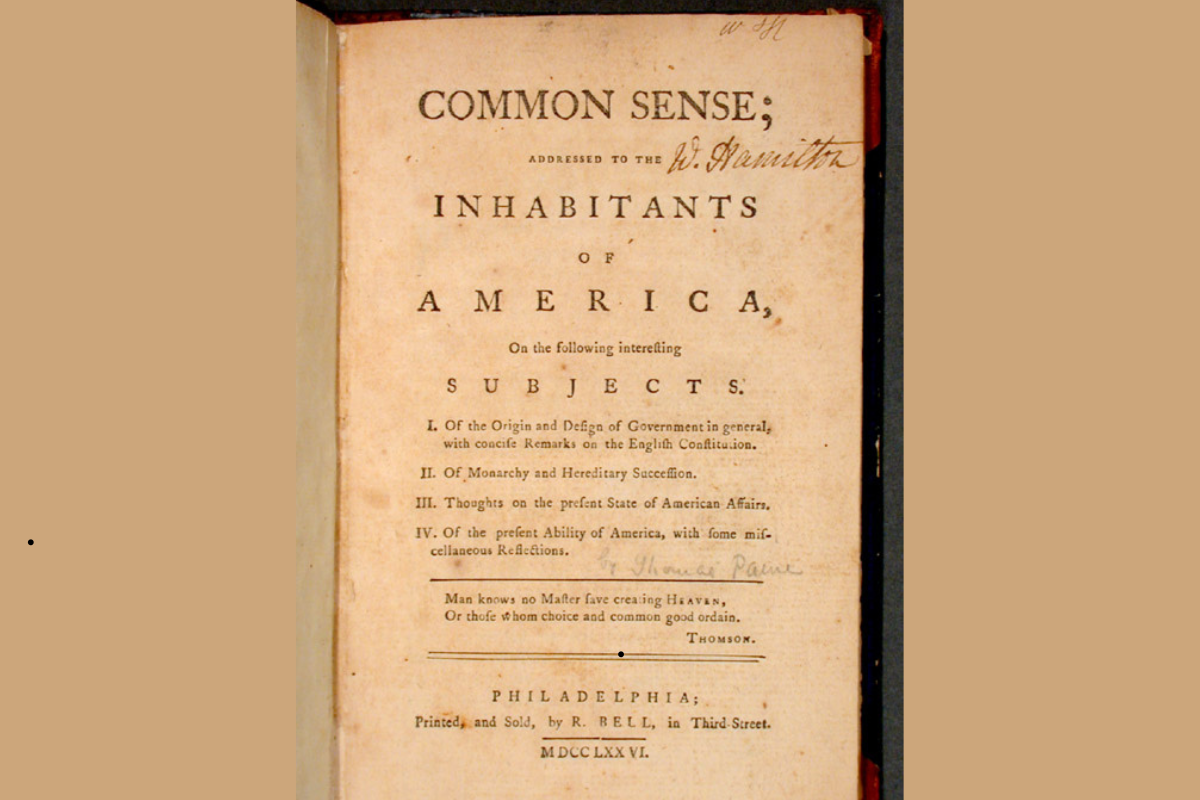

What Americans have inherited instead is a small-r republican notion of freedom. Philip Pettit calls this “freedom as non-domination.” You can think of freedom in terms of a bunch of doors, and your choice about which one to walk through (this is Isaiah Berlin’s metaphor). Where liberal freedom means the doors are open, and democratic freedom means you get to close doors when you win elections, republican freedom

“require[s] that not only should each door be open; it should also be the case that no one is positioned to close it, should they wish, against the agent. There should be no doorkeeper on whose goodwill the agent has to depend for permission to pick any particular door. In other words, there should be no one with the power of a master or dominus over how the choice is exercised. In order to be free in that choice, not only should no one else interfere with its exercise, no one should even have the power of interfering in that way. The agent should enjoy the absence of domination, whether or not the domination leads to interference.”

When people on both sides complain about the creeping loss of freedom, the advance of “fascism” on the other side, they typically use that language of “liberal democracy” to explain what it is they sense is happening. When they’re being precise, the complaint on the right is that democracy – the will of the majority, even if it is “silent” – is being quashed by liberals and their obsession with “rights.” When they’re being imprecise, which is most of the time, the right will talk about how they are “defending their rights,” not noticing that rights are limits on democracies. Conversely, when they’re being precise, the complaint on the left is that liberalism – the protection of individual rights or group rights – is being threatened by populist democrats and their obsession with “imposing values.” When they are being imprecise, which is also most of the time, the left will talk about how they are “defending democracy,” not noticing that democracy means being able to abrogate rights in order to impose the majority’s values.

The rhetorical confusion comes from the way we’ve fused the two terms, but the logic of each term lines up pretty well with the actual substance of each side’s positions, and it is not too hard to sort out. The real confusion produced by the reliance of both sides on the concept of “liberal democracy” is that they don’t recognize the kind of freedom that is actually being lost, which is not so much democratic freedom or liberal freedom as it is republican freedom.

Part of the trouble is that our republican freedom is being eroded not so much by “the government,” which Americans are primed to distrust (at least when their side isn’t running it), as it is by the institutions that constitute what Elizabeth Anderson calls “private government.” Anderson has corporations in mind; she is talking about the ways that employers micromanage the lives of their employees. Starbucks using algorithms to adjust work schedules is a good example. Rather than a set shift, baristas are always on call, which means they have to plan their lives around the arbitrary and unpredictable will of the bosses. Even if the actual government is still democratic and liberal, most Americans work for corporations, and spend most of their lives at work. They have far more daily contact with their employer than with any agent of “the government,” and this means that they are effectively subjects of a government in which they have no representation.

I’m not sure why Anderson confines her analysis to greedy for-profit corporations when it obviously applies just as well to nobler institutions like schools and hospitals. Americans spend the whole first quarter of their lives at school. We can hope to spend less of our lives in hospitals, but the same is true when you find yourself sucked into that system. Anybody who has spent any time in such a place knows that feeling of being dominated by people with permission slips. Anderson’s insight into “private government” needs to be supplemented by Foucault’s famous rhetorical question: "Is it surprising that prisons resemble factories, schools, barracks, hospitals, which all resemble prisons?" They resemble each other not least because they are sites of domination.

At least when it comes to the city and its untoward interest in my deck repairs, I can recognize a genuine public interest being served by people who are eventually accountable to elected officials, who are themselves eventually accountable to me and other citizens. The same is not true in the various non-governmental institutions that more directly shape our day-to-day lives. The widespread experience of being smothered is what explains why so many people reacted with such glee when the head of HR was caught snuggling with the CEO on camera at the Coldplay concert. “Human Resources” is a perfect example, and has become the perfect symbol, of the loss not of “freedom” in general but of republican freedom in particular. The idea that two adults need permission from HR to go on a date is enraging. It doesn’t matter if in practice the permission is always granted. It doesn’t matter if it’s “just a form to fill out.” The fact that it’s “just a form” is precisely what makes it so enraging, and so satisfying when the enforcers turn out to be hypocrites. There’s an unhealthy element of schadenfreude in the public’s reaction to the Coldplay video, but there’s also evidence of a healthy desire for a more republican way of life – one lived under the rule of law, but not under the rule of managers.

Assistant Professor of Political Philosophy at the University of Dubuque

Related Essays