The Post-Literate Republic

In Gary Shteyngart’s 2010 comic dystopia Super Sad True Love Story, a middle-aged man of the future who still reads physical books falls in love with a younger woman who knows nothing but digital “content.” Near the beginning of the story, the man is nervously preparing for the young woman’s first visit to his apartment.

I counted the volumes on my twenty-foot-long modernist bookshelf to make sure none had been misplaced or used as kindling by my subtenant. “You’re my sacred ones,” I told the books. “No one but me still cares about you. But I’m going to keep you with me forever. And one day I’ll make you important again.” I thought about that terrible calumny of the new generation: that books smell. . . . I decided to be safe and sprayed some Pine-Sol Wild Flower Blast in the vicinity of my tomes, fanning the atomized juices with my hands in the direction of their spines.

Twenty-five years later, the new generation has arrived. Last year’s widely-circulated report on “the elite college students who can’t read books” put a fine point on the many studies now suggesting that since the introduction of the smartphone (called an “äppärät” in the novel), Shteyngart’s post-literate America has moved rapidly from imagined future to present reality.

Post-literacy, to be clear, does not necessarily mean that people can’t decipher the written word. A post-literate society is one in which people don’t read, not one in which they literally cannot (though it is terrifying to consider that actual reading proficiency has also declined for the first time in recorded history). More specifically, it’s a society in which people don’t – and therefore can’t – read anything that’s “too long,” which is how many of my own students describe any text longer than a few paragraphs.

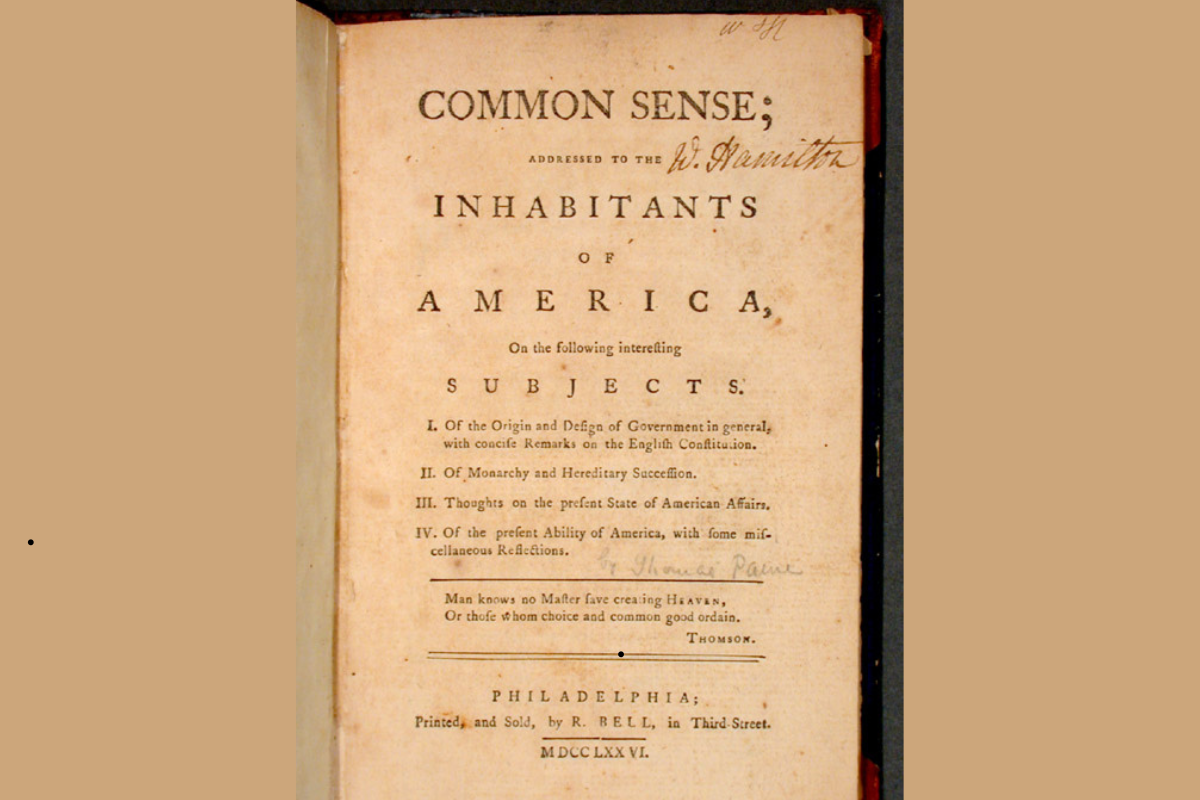

There’s a long history of ideas about the connection between habits of reading and forms of government. Benedict Anderson argued that the modern nation-state itself was a creation of the printing press, which enabled readers to join “imagined communities” that existed first on the printed page and only afterward in real life. Theorists like Martha Nussbaum and Richard Rorty have emphasized a special link between fiction-reading, in particular, and the democratic or republican form of the modern nation-state. And of course the instistence that a republic requires an “educated citizenry” is readily found in the Founding Fathers, for whom education was mainly a matter of reading books – something that remained true until very recently. “I cannot live without books,” wrote Jefferson. Can a republic?

It’s not easy to defend the argument that “good citizens read books,” since you can always find examples of bad citizens who are well-read and good citizens who aren’t. But it’s hard to deny the intuition that in some sense it must be true. Super Sad True Love Story is not unique in its attention to the fate of books in a dystopia. Sometimes books are suppressed and destroyed, as in 1984; sometimes they are ignored and forgotten, as in Brave New World. It’s easy for a certain type of mind – the type that automatically divorces “content” from form, message from medium – to assume that in these stories, the book is just a symbol for “knowledge,” and that as long as we still have access to and interest in “knowledge,” we cannot be said to live in a dystopia. This type of mind also tends to remember Orwell’s lesson while forgetting Huxley’s. In 1984, “ignorance is strength,” while the brave new world is made possible by genuine (though dogmatically utilitarian) scientific knowledge. Since in the real world of 2025 nobody is raiding libraries and burning books (despite the annual efforts of book-sellers to attract customers by pretending that “banned book week” celebrations are part of la Resistance), and since everybody has limitless access to all the world’s knowledge via devices that are the fruits of genuine (though, again, dogmatically utilitarian) scientific knowledge, it’s easy for this sort of optimist to imagine that demise of book-reading is just the rise of reading in new forms.

But there are good reasons to believe that it’s the form that makes the difference. Times critic James Marriott argues that “we are living through one of the great shifts in cultural history. To future historians the most distinctive cultural feature of the 20th century will not be cinema or jazz but . . . mass literacy,” and that this era is now coming to a close as literacy gives way to something like an oral culture built mainly around the consumption of short video clips. Drawing on Neil Postman, Marriott suggests that “[t]he habits of sustained attention, logical argument, and calm impersonal communication are fundamental to a democratic society. All modern democracies are products of the highly literate societies of the nineteenth century. Without literacy, democracy may not survive.”

Democracy, however, might survive just fine. I know what Marriott means by “democracy” – something like “a free society” – and I don’t want to be pedantic. But the stakes of declining literacy would be clearer if we emphasized that the threat is not to the ability of the people to participate in the debates and decisions that affect them, either directly by voting on the issues or indirectly by voting for representatives. Our devices make it easier than ever to access the process, and it is not hard to see how it might get even easier. Nor is the threat to people’s interest in participating; social media is very good at generating “interest” (though it may also substitute the feeling of being “engaged” for the actual work of engagement). The threat is rather to the activity in which we are (or are not) participating.

The politics of the book looks very different from the politics of TikTok, even if “BookTok” is one of TikTok’s most popular hashtags. Crucially this has nothing to do with people’s “politics,” in the sense of their political opinions. The end of literacy does not necessarily change minds or introduce new ideas, though we are certainly living through a period of ideological ferment and factional realignment. What it changes is not what people think but how they think it, how they come to think it, and how they communicate it to others. A post-literate America is one in which politics is made by people whose attention is not sustained by reading books but fractured by consuming bite-sized bits of infotainment, whose arguments are not disciplined by the expectation that they make logical sense but are simply accepted or rejected according to their marks of tribal identity, and whose communication style is neither calm nor impersonal but hectic and “authentic,” a style that aims not to persuade but to go viral. In a post-literate America there will still be conservatives and liberals and Marxists and libertarians and everybody else. But their debates will sound nothing like even the ones I grew up with in the pre-Internet era, let alone the Lincoln/Douglas debates that everybody always holds up as the ultimate example of what ordinary citizens used to be capable of. They’ll sound like last year’s presidential “debate” between senility and vulgarity.

Post-literate politics can certainly be democratic. It can probably be more democratic. What it cannot be is the politics of a democratic republic, which requires not just an involved but a virtuous citizenry. John Adams’ much quoted claim that “[o]ur Constitution was made only for a moral and religious people” and “is wholly inadequate to the government of any other” is not irrelevant here, if we can entertain the possibility that morality and religion as Adams understood them were made only for a literate people. This idea too has a long history of development. Walter Ong’s famous Orality and Literacy, for example, explores the changes to religious and moral consciousness (and to the very meaning of those terms) wrought by the shift from oral cultures to cultures of the printed word.

It is often suggested that the present shift to a post-literate society is really a shift back to an “oral” society. Videos and podcasts, after all, are all about the spoken rather than the written word. It is also suggested that oral cultures have their own virtues, and that print cultures have their own vices. “The letter kills, the spirit gives life.” Literacy can encourage literalism, a fundamentalism about texts that encourages intolerance. A post-literate society, if it is an oral society, will certainly be different, but perhaps it is no less capable of being a republic than Rome, which was certainly not filled with average-Joe book-readers.

The problem, as philosopher Jared Henderson has pointed out, is that oral cultures prioritized memory. An enhanced capacity for memory is one of the virtues of an oral culture, just as an atrophied capacity for memory is perhaps one of the vices of a print culture (Plato thought so). But a post-literate society is not one in which people stop reading books because they commit them to memory. It’s one in which nobody can remember anything at all. Our devices are actively destructive of our memories, to the point that researchers now speak of “digital amnesia” (and even “digital dementia”). When we lose both the capacity to write moral and religious principles on our hearts and the capacity to wrestle with the books in which those principles are developed and contested, what happens to the morality and religion that Adams considered so necessary to the health of a republic?

In Shteyngart’s novel, post-literate America does not end well. It’s just a book, of course, and a very funny one. There’s more room for hope in reality than in stories. I actually suspect books will “become important again,” even if they will always be “just books.” But I think they’ll only be important for a small group of readers, and I don’t think that group will form some kind of enlightened minority capable of leading the benighted masses. More likely they’ll just be throwbacks and weirdos like Shteyngart’s protagonist, wasting time with their “smelly” tomes, and probably writing whiny articles about The Good Old Days for websites devoted to the memory of a president the kids have never heard of.

Assistant Professor of Political Philosophy at the University of Dubuque

Related Essays