Plessy v. Ferguson (1896)

An Oklahoma City streetcar terminal's "colored" drinking fountain, 1939

Introduction

Even casual followers of Supreme Court history are likely familiar with the constitutional canon – Marbury, McCulloch, Brown v. Board and a handful of other cases that over time have acquired a near-mythical status in shaping the long arc of constitutional jurisprudence that followed. The entries in the canon carry a foundational authority that extends well beyond mere doctrine or legal reasoning into the realm of the symbolic. Dred Scott and the Civil Rights Cases, in contrast, represent something of an anti-canon; marked by highly suspect legal reasoning, having enormous deleterious practical consequences, hardening racial discrimination and oppression, they are reviled on a level that puts them in what Ilya Somin has labeled the Supreme Court’s “Hall of Shame.” The other late 19th Century decision that warrants a place in the anti-canon is Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), in which the Court stamped legally imposed racial segregation with its imprimatur, thus providing constitutional cover to Jim Crow arrangements that would pervade American life into the mid-20th Century.

The Supreme Court of the 1880s and ‘90s was a liberty-minded body, but mindful mostly of liberties other than those that drove the enactment of the post-Civil War Amendments. The Court focused much of its energy during that time to protecting the private property interests of high finance, industry and corporate American. Meanwhile the Court in the Civil Rights Cases denied that the Reconstruction amendments provided any basis for attacking discrimination by private actors, showing little interest in ensuring or extending broad-based equality to freemen and Black citizens. The Court would take its logic a step further in Plessy, concluding that even action by the state of Louisiana that separated rail travel along color lines failed to offend the 13th-15th amendments.

Racial Discrimination in Rail Travel: From Reconstruction to Jim Crow

Racially segregated transportation in America had a long history, predating the Civil War by several decades. The subordinate status of Blacks was reflected in their exclusion from or limited access to public transit. At the same time, those restrictions were the focus of contestation and civil disobedience. Frederick Douglass’s refusal to leave a white railcar in Massachusetts in 1841 provoked widespread protests and led that state in 1843 to enact the first ban on racial discrimination in public transport. Resistance to segregated railcars followed in cities in the east and north. By the end of the Civil War, segregated streetcars had come to an end in Washington D.C. and elsewhere.

New Orleans and Louisiana were emblematic of the currents that swirled around race and movement in public transportation, with a twisty tale of political victories followed by setbacks. Up to and during the Civil War, New Orleans’ private street car companies had maintained a system of segregation, with cars for Blacks marked with a star. The system faced deep opposition, with Star Cars the target of longstanding Black protest. With the end of the war and the onset of Reconstruction, segregated streetcars disappeared. The new Louisiana Constitution of 1868, which enshrined “civil, political, and public rights” for all citizens of the state regardless of color, specified that all public conveyances and accommodations were to be “opened to the accommodation and patronage of all persons, without distinction or discrimination on account of race or color.” Homer Plessy, born in New Orleans in 1863 to French free people of color, would have entered his teen years attending integrated schools and riding integrated public transportation.

By the time Plessy had reached adulthood, that had changed. The formal demise of Reconstruction would bring reversals, as conservative white Democrats quickly gained power in Louisiana. The new government began to dismantle the gains of Reconstruction, beginning with integrated schools. Another new constitution in 1879 struck language guaranteeing equal rights in public places and ended public school integration. It would take about a decade for Jim Crow laws to take over public transit. By 1890 laws resegregating rail cars had begun to proliferate, with nine states passing Jim Crow laws in the area of rail transportation between 1887 and 1892. In 1890 Louisiana passed the Separate Car Act, which mandated all trains to “provide equal but separate accommodations for the white, and colored races, by providing two or more passenger coaches for each passenger train.” No person was “permitted to occupy seats in coaches, other than the ones assigned to them on account of the race they belon to.”

Challenging the Separate Car Act: The First “Interest Group” Litigation?

Even before the Separate Car Act had passed, it was attracting opposition. New Orleans was known for its robust civil rights activism during and after the Civil War. A coalition of French speaking Creoles, Blacks and their white radical Republican allies actively pushed for civil rights laws during Reconstruction and fought against legal rollbacks once Reconstruction had collapsed. A young twenty-something Homer Plessy would join one such group (the Justice, Protective, Educational and Social Club), rising to the position of vice president. Opposition to forced resegregation through mass protests and lawsuits continued into the 1880s, even as it proved increasingly futile.

A Black activist newspaper, the Crusader, had launched in 1889, paying special attention to proposed laws that might further chip away at civil rights. It would join forces with the Louisiana chapter of the American Citizens’ Equal Rights Association (ACERA), a national organization founded in 1866 to work to advance racial equality through voting rights and other civil rights legislation. Within a year of the passage of the Separate Car Act, leaders of ACERA in New Orleans organized the Citizens’ Committee to Test the Constitutionality of the Separate Car Law. It was one of the first known instances of what later would be called “interest group” litigation, where an advocacy or activist organization planned a test case for purposes of challenging the constitutionality of a law.

Before the Citizens Committee organizers even had a plaintiff, they had settled on Albion Tourgee to litigate the challenge to the law. Tourgee was a carpetbagger from New York who, after serving as a Union army officer in the war, moved to North Carolina during Reconstruction to help draft their new state constitution and where he would subsequently serve as a judge. With the disintegration of Reconstruction, Tourgee returned to New York, where he acquired a reputation as a militant and outspoken advocate for racial equality. He also was regarded as the leading civil rights attorney in the country. He ultimately would represent Homer Plessy free of charge.

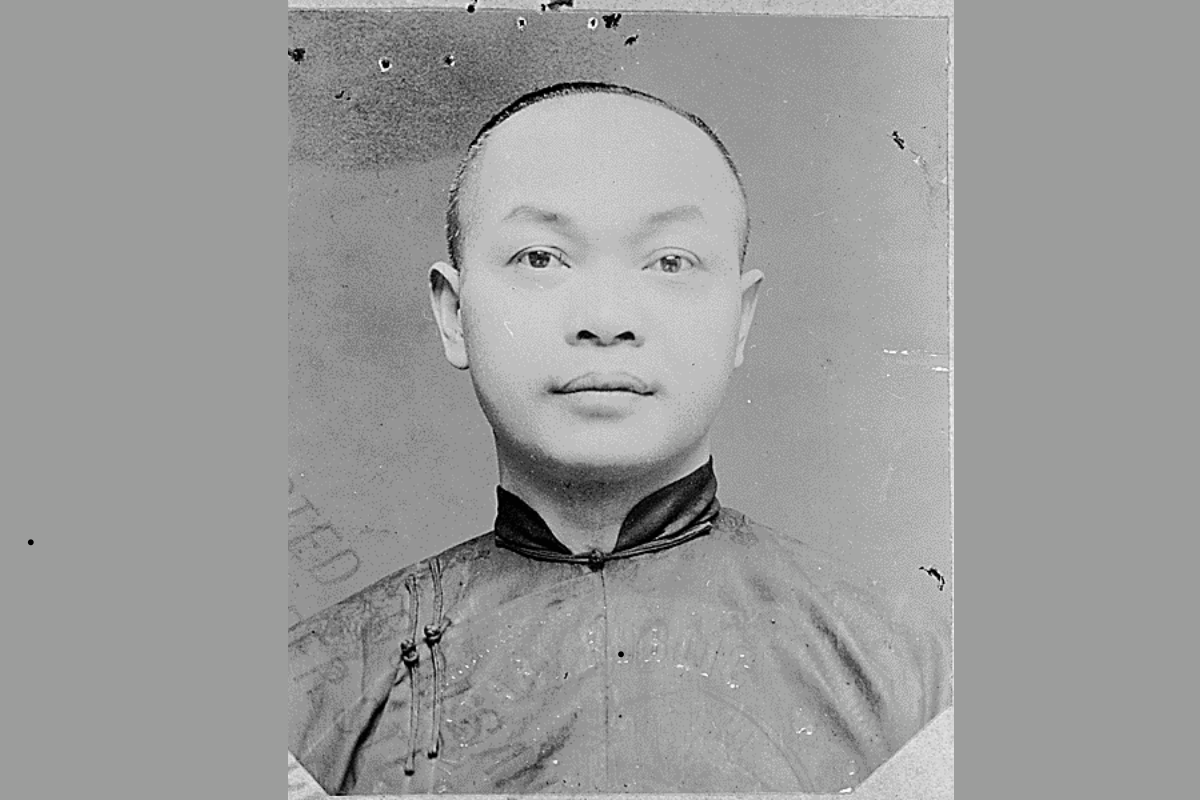

Tourgee sought a lead plaintiff who was not more than “one eighth colored blood,” whose appearance he hoped would expose the ambiguities of the race categorizations. Homer Plessy fit the bill. He was of French Creole descent, described in court filings as someone whose “mixture of colored blood” was not readily discernible. In other words, he could pass as white. Tourgee and Plessy worked in concert with the railroad officials to plan the details of the ride that would lead to his arrest. Most railroads opposed the Separate Car Act, which negatively impacted their business.

Plessy’s Journey from the Rail Car to the Supreme Court

Homer Plessy’s lengthy odyssey to the Supreme Court began in June 7, 1892 with his purchase of a first-class ticket at the New Orleans station of the East Louisiana Railway. Plessy took a seat in a coach exclusively for white passengers. When the conductor ordered him to move to a car for passengers “not of the white race,” Plessy refused. He was taken out by a police officer and transported to the parish jail of New Orleans. In July of 1892 Plessy was formally charged with violating the Jim Crow law. By November the trial judge had rendered the expected ruling rejecting Plessy’s arguments under the 13th and 14th amendments. After a series of legal machinations, the case landed in front of the Louisiana State Supreme Court, which upheld the trial court ruling on January 2, 1893. Within days, Plessy’s lawyers sought a writ of error from the state Supreme Court, which issued the writ the same day. The legal filings arrived at the High Court by the end of February 1893.

Plessy’s case had progressed quickly, getting to the Supreme Court within eight months of his arrest. Upon reaching the High Court, it would languish untouched for over three years. In part, the Court faced a daunting docket, one where it decided almost 400 cases in a single year (1895). Nor was attorney Tourgee in any hurry for the Court as it was currently constituted to take up his case. Counting votes gave him little optimism his client could prevail. He was happy to let the case sit, in hope that changes might materialize either in the Court’s personnel or in the political landscape around race matters that could strengthen his hand.

Alas, the political and legal environment was no more hospitable when the Court took up the case in 1896. If anything, public sentiment had only grown more hostile to the plight of Blacks. Jim Crow had continued to advance across the South. Congress had undone virtually all of the remaining statutory remnants of Reconstruction. Few could have been surprised when the Court issued a ruling on May 18, 1896 upholding the Louisiana law by a 7-1 vote, with only the intrepid Justice Harlan dissenting.

The Majority Opinion

The unremarkable Justice Henry Brown wrote for the majority, in what was his lone major opinion in his 15-year stint on the Court. Brown perfunctorily dispensed with the 13th amendment claim that Jim Crow represented a “badge of servitude.” It was “too clear for argument” that “the ownership of mankind as a chattel” was the singular aim of the amendment. In the three paragraphs he devoted to this argument, Brown relied on the Civil Rights Cases, conveniently ignoring the fact that those disputes involved private discrimination and not the state action at issue in Plessy.

Turning to the 14th amendment, Brown engaged in a series of sophistries to avoid applying the amendment to the Separate Cars law. Recognizing that the aim of the amendment was “undoubtedly to enforce the absolute equality of the two races before the law,” he concluded that the law did not in fact “discriminate” on racial grounds, but merely recognized a “legal distinction between the white and colored races.” Such distinctions had no tendency to destroy the legal equality between the races, and in fact “must always exist so long as white men are distinguished from the other race by color.” He also drew a line between the amendment’s application to political versus social equality. “[I]n the nature of things [the amendment] could not have been intended to abolish distinctions based on color, or to enforce social, as distinguished from political, equality, or a commingling of the two races upon terms unsatisfactory to either.” Brown differentiated between deprivations of Blacks’ political rights from “those requiring the separation of the two races in schools, theatres and railway carriages.” As legal authority, Brown relied on Roberts v. City of Boston, a Massachusetts state supreme court decision that preceded the passage of the 14th amendment by several decades. The Roberts decision also involved school segregation that was a matter of choice, rather than legally imposed in the fashion of Jim Crow. In other words, the precedential weight behind Brown’s line between social and political equality was weak at best and non-existent at worst.

The implicit racism of Brown’s opinion became more pronounced once he moved beyond the constitutional arguments in search of legal justification for the Jim Crow law. He found his rationale in the police powers of the state, its reserved authority to act generally to ensure the public health, safety, welfare and morals of the people. Legal separation of the races fell within the exercise of the state’s police power, which extended to laws passed in good faith for the “promotion of the public good, and not for the annoyance or oppression of a particular class.” The Court cited no actual instances of public order being undermined by integrated rail cars, nor did Brown specify what elements of public well being or morality were advanced by separate train cars. To meet the low bar of “reasonableness,” he simply granted the state “large discretion” to act pursuant “to the established usages, customs and traditions of the people, and with a view to the promotion of their comfort, and the preservation of the public peace and good order.” Naturally the comfort and customs at issue were assuredly those of the whites who preferred not to share railcar space with their Black fellow citizens. Racial harmony could not be achieved through law, especially “by laws which conflict with the general sentiment of the community upon whom they are designed to operate.” The Constitution could not compel the “commingling of the two races upon terms unsatisfactory to either.” By this measure, the racial animus of whites toward blacks could suppress anti-discrimination efforts in the sphere of public accommodations indefinitely (which in fact was what happened).

As the Court had done in the Civil Rights Cases, when Justice Bradley piously lectured the plaintiffs for what he called their expectation of special treatment, Brown too could not resist closing his opinion by placing the blame for any racial indignities that might be provoked by the law on Blacks themselves.

We consider the underlying fallacy of the plaintiff’s argument to consist in the assumption that the enforced separation of the two races stamps the colored race with a badge of inferiority. If this be so, it is not by reason of anything found in the act, but solely because the colored race chooses to put that construction upon it.

The Harlan Dissent

In his most famous dissent, Justice Harlan offered a point-by-point rebuttal of the majority opinion, first taking direct aim at the majority’s crabbed reading of the 13th amendment. He contended that the amendment did more than strike down the institution of slavery. Rather it “decreed a universal civil freedom” for all people, and stood as a bar to “any burdens or disabilities that constitute badges of slavery or servitude.” Harlan flatly concluded that the “arbitrary separation of citizens, on the basis of race, . . . is a badge of servitude wholly inconsistent with the civil freedom and the equality before the law established.” It was clear to him that the Separate Car Ace put “the brand of servitude and degradation upon a large class of our fellow-citizens, our equals before the law.”

Harlan then turned his attention to the 14th amendment. He dismissed the abstract formalism of the Court’s contention that the law hurt neither race more than the other. Harlan rightly saw the law for what it was, a debasement and degrading of Blacks. He scornfully declared that everyone knew the statute’s purpose was to “exclude colored people from coaches occupied by or assigned to white person.” It was a “thinly disguised” means of asserting the supremacy of one class over another.

Harlan linked 14th Amendment equal “protection” to equal “citizenship,” as articulated in the opening words of the amendment; it was “all citizens [who] are equal before the law.” (emphasis added) Hence there was no difference between rights in their political or social context. Harlan referred more broadly to “civil rights” to protect Blacks against discrimination in all places that might be touched by state regulation. The amendments were designed to protect Blacks in their enjoyment of all those civil rights their White counterparts enjoyed. To make the point, he offered one of the most-cited and famous lines in Supreme Court history.

But in the view of the constitution, in the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste here. Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights all citizens are equal before the law.

As Akhil Reed Amar has noted, the revolutionary nature of Harlan’s dissent lay in an integrationist vision that was remarkable for the time. He declared “[t]he destinies of the two races, in this country, . . . [to be] indissolubly linked together, and the interests of both require that the common government of all shall not permit the seeds of race hate to be planted under the sanction of law.” The amendments taken in toto “removed the color line from our governmental systems” throughout. No public authority could ever “know the race of those entitled to be protected in the enjoyment” of their constitutional rights.

Once again, the prescience of Harlan the Great Dissenter was on full display. He closed his opinion by stating his expectation that “the judgment [of the majority in Plessy] rendered this day will, in time, prove to be quite as pernicious as the decision made by this tribunal in the Dred Scott case.” The place occupied by Plessy v. Ferguson in the modern-day anti-canon attests to the accuracy of his prediction.

The Consequences of Plessy v. Ferguson

The decision hardly generated a ripple in the popular press. Of fifty-two cases reported on the same day as Plessy, three found their way onto the front pages of the New York Times, dealing with contract law, inheritance and copyright, respectively. Plessy merited a lone reference on the inside pages under the subject of railway news. The case warranted nary a mention in the exhaustive Supreme Court history that came out several decades later, authored by the then-leading Court historian Charles Warren. It would not start working its way into law school casebooks until well into the 1940s. In other words, the decision was regarded as routine, normal, an unremarkable reflection of the racial logic of the time.

The social and legal context for Plessy was racial segregation as a normatively accepted fact. It was a given in public and private life, a social and political reality, a product of law and custom. With the exception of Justice Harlan, the Plessy Court operated wholly within that normative frame. The anti-canonization of the decision lay in its perpetuation of segregation long into the future. The Court’s stamp of approval of Jim Crow guaranteed the country would have a much harder time moving beyond it. The Civil Rights Cases provided the foundation for the codification by southern states of what had theretofore been mere practice of private racial discrimination. Plessy was the bookend a decade later that allowed for the building of the edifice of legalized segregation and subordination of blacks in housing, education, work, and virtually all facets of public life.

The Separate Car Act’s mandate of “separate but equal” facilities would become the standard for judging Jim Crow laws, despite the obvious fiction of the “equal” part of the calculation. Only when the Warren Court determined in Brown v. Board in 1954 that “separate was inherently unequal” did Jim Crow’s house of cards quickly crumble.

A Postscript

Plessy involved a roster of fascinating characters – the ex-carpetbagger Tourgee, the ex-slaveholder Harlan, and Plessy himself, the light-skinned Black protagonist at the center of the story. Another intriguing figure who would make several cameos in the unfolding saga of the legal dispute was Francis Nicholls, without whom the case might never have made it to the Supreme Court. Nicholls was a Louisiana native; he served in the Confederate army, where he rose to the status of general. He suffered several serious wounds in battle that led to the loss of an arm, a leg, and an eye. He would go on to an impressive political and legal career that included the governorship of Louisiana, president of the American Bar Association, and Chief Justice of the Louisiana Supreme Court.

Nicholls’ first appearance came when he, as governor of Louisiana, signed the Separate Car Act into law in 1890. His governorship could be traced back to the long arm of the contested 1876 presidential election and the Compromise of 1877 that put Rutherford Hayes in the White House and led to the withdrawal of the federal presence in the south. Nicholls’ run for the governorship was an eerie parallel to that of the presidential election; the result was too close to call, with both Nicholls and his Republican opponent, Stephen Packard, claiming victory. Both candidates were sworn in on the same day, leading to a bizarre constitutional crisis that would last for four months. It ended only when Hayes’ withdrawal of federal troops from the South led to the collapse of the Black suffrage, and with it Packard’s gubernatorial bid. Nicholls took office in 1877 with a promise to “obliterate the color line in politics” and he acted benevolently toward Louisiana Blacks. Indeed the leaders behind the Plessy lawsuit later credited him for initially securing “a degree of protection to the colored people not enjoyed before under republican Governors.” The new Louisiana constitution of 1879 prematurely ended Nicholls’ term, and he returned to his law practice in 1880.

Nichols would return to the governorship in 1888 under markedly different circumstances. His signing the Separate Car Act into law in the middle of his second term was a clear sign of how much the terrain had changed due to the disappearance of federal enforcement of civil rights and the perceived segregationist concessions that the racial politics of the moment required. Nicholls would reappear later in the story. When he left the governor’s mansion a second time in 1892, he was named Chief Justice of the Louisiana Supreme Court, a position he held for twelve years. In that capacity he would the state Supreme Court that rejected Plessy’s appeals; he would personally sign the order that sent the case to the U.S. Supreme Court. Nicholls passed away in 1911. Nicholls State University in Thibodeaux, Louisiana carries his name to this day.