Federalist 55 Part I

At the beginning of Federalist 55 Madison correctly states that no issue caused more controversy at either the Constitutional Convention or the state ratifying conventions than the question of how many representatives should serve in the House. He also correctly observed that the issue admitted of no exact numbers. Too few representatives and popular interests are disregarded, too many and the assembly becomes unruly and unmanageable. This latter point nodded to the general consensus concerning the unruly nature of democracy itself.

One of the ironies of our current situation and commentary on it is that those most zealously guarding “our democracy” against its perceived “threats” tend not to see that the problems they worry about are expressions of democracy. Granted, there are some serious dangers afoot, but large swaths of the population resisting the machinations of their “superiors” is an expression of democracy, especially when those elites cloak their maneuvers in the shawl of democracy.

A Republic, Not a Democracy

The framers of our constitution understood this tendency which is why they insisted on a “republican” form rather than a “democratic” one. Here’s where things get complicated, for no surer defenders of republicanism existed than many of the Anti-federalists, who also shilled for a more expansive assembly. Their argument for decentralization hinged in no small part on the significance of virtue in both the citizenry and their elected officials. Furthermore, it’s difficult to affirm a person’s character if you’ve never met that person, and you can’t rely on that person to represent the interests of a place and its people if the representative is not from there.

The dangers of democracy intensify when on a larger scale. If western Massachusetts gets unsettled by some unrest, well, that is their problem (if indeed it be a problem at all). The pathogen can be contained. Rescaling allows the pathogen to spread rapidly and widely. One need not be a keen observer of human nature to realize that people behave differently when in the presence of others, and really behave differently when part of a large gathering, such as a sporting event. They tend to take on the characteristics of the crowd, often abandoning their instinct to self-restraint, good manners, and sound mores. Even the most virtuous of people can find it difficult to resist the madness of crowds. Or, as Madison shrewdly put it in 55, even if every Athenian were a Socrates, every Athenian assembly would still be a mob. This receives my vote for best single line in all The Federalist.

Keep in mind that while republicanism had a good reputation among political thinkers, democracy did not. Plato had described it as about the worst form of government and one that inevitably leads to tyranny. He explained that because democratic persons lacked the virtues necessary to govern themselves, giving in constantly to their desires and lusts, someone would have to come in and imposed order on the chaos. A libertine people cannot be free — “their passions forge their fetters.”

Popular Sovereignty

You can’t do republican government, however, without its legitimacy grounded somehow in the will of the people. Republican thinkers like to think of self-government in two senses: to exercise self-control and to engage mutually in community building. Thus it was always thought that republicanism could only exist on a small scale among people who could see the issues at hand, know specifically how to address them, understand who could be commissioned to handle situations well, all grounded in feelings of mutual solicitude and a desire to do the right thing. Mobs destroy relationships; republican virtue and neighborliness cultivates them. Virtue, intimacy, and trust all mutually uphold each other. Any severing, stretching or straining of the relationship between principals (people) and agents (elected representatives) necessarily gets us closer to either tyranny or anarchy.

The maintenance of that relationship is thus the sine qua non of any system of republican government, and thus the debates could not have been more consequential. The Anti-federalist case was clear: if the proportions were too few representatives to too many citizens, the representatives will no longer fairly and justly represent their constituents and, worse still, will fall prey to some kind of “foreign” influence, in this case meaning simply “not of that place.”

Pernicious Influences

Eisenhower warned the nation of a powerful “foreign” influence growing in its midst: the military-industrial complex. Indeed, there is not a congressional district in this country not touched by it, even if the denizens of those places had wished it so. Without sufficient representation smaller places would be prey for powerful interests. Thus Brutus observed that “on a careful examination, you will find, that many of its [the Constitution’s] parts, of little moment, are well formed; in these it has a specious resemblance of a free government – but this is not sufficient to justify the adoption of it – the gilded pill, is often found to contain the most deadly poison.” The parts of major consequence, however, gave away the lie. Representation in the House, he claimed, only displayed “a feint spark of democracy” and did not possess “the qualities of a just representation.”

“It has been observed,” he continued, “that the happiness of society is the end of government – that every free government is founded in compact; and that, because it is impracticable for the whole community to assemble, or when assembled, to deliberate with wisdom, and decide with dispatch, the mode of legislating by representation was devised.” In order for that to work those elected “must resemble” those who voted for them. In a particularly apt turn of phrase, he noted that a stranger to our country should be able to look at the House of Representatives and have a clear picture of the people of the nation. Could that possibly happen now, where 31.7% of house members and 47% of senators have law degrees? How well are the nation’s food interests — which we must agree is not an inconsequential interest, even if it’s a small part of GDP — represented when there are only 33 persons on the Hill with any background in farming? And this is to say nothing of the composition of Congress when it comes to race and sex and socio-economic status.

Brutus goes beyond mere accidental characteristics, however. Representatives “should possess … the sentiments and feelings” of the people they represent, and those in turn connect directly to the habits and mores of the places they’re from. Only in a deracinated society would that sense of place no longer matter. Any government should only act when it can do so in the interests of the whole, but Brutus and others worried that, under the system of representation on offer, only some of the parts would benefit. Quick: name as many representatives and senators as you can, and tell me how many come from the heartland.

Too Few Representatives

The paucity of representatives, fixed by the constitution at 1 per 30,000, concerned the Anti-federalists. “The house of assembly,” Brutus continued, “which is intended as a representation of the people of America, will not, nor cannot, in the nature of things, be a proper one — sixty-five men cannot be found in the United States, who hold the sentiments, possess the feelings, or are acquainted with the wants and interests of this vast country.” New York’s six representatives could not possibly advance all the interests of the different classes and occupations that made up a very diverse New York state in 1788. Even if six such persons could be found, could they be elected, or would wealth, as it always does, distort the electoral process?

And wouldn’t family-wealth, passed on from generation to generation, create a new aristocracy, a new form of hereditary rule that would have all the vices and none of the virtues — particularly a sense of obligation to those below them — of the old landed nobility? What would Brutus make of the Cuomos? Power, wealth, and privilege would count for more than virtue and a decent respect for one’s neighbors. Service in the House, Brutus worried, “…will and must be esteemed a station too high and exalted to be filled by any but the first men in the state, in point of fortune; so that in reality there will be no part of the people represented, but the rich, even in that branch of the legislature, which is called the democratic. – The well-born, and highest orders in life, as they term themselves, will be ignorant of the sentiments of the midling [sic] class of citizens, strangers to their ability, wants, and difficulties, and void of sympathy, and fellow feeling.” The already wealthy would be able to use the coercive power of government, not to support the yeomanry and the small business owners and others similarly placed, but to plunder the wealth of the middle class while protecting their own.

Here’s Brutus’s thought-experiment in modern terms: the House of Representatives, currently consisting of 435 voting members, needs 218 for a quorum. A simple majority vote of 110 could carry a bill successfully to passage. This means that a nation of 340 million persons could effectively be governed, and taxed, by 110 people, strangers to nearly everyone.

Right now each member of the House represents, on average, nearly 800,000 constituents. Should the Constitution’s stipulated number of no more than 30,000 be followed there would be roughly 11,300 members of the House. Defenders of this malapportionment argue, as Madison did, that these numbers would be too unwieldy, rendering Congress impotent. Even so. But Congress is hardly a functional body the way it is, and in any case the main purpose of the House is not “to get things done” but to represent the great variety of American life and allow each and every class of citizen a voice in the process, even if, maybe especially if, it yields no result.

We have it on great authority that the compromise number of 30,000 was to be regarded as sacrosanct. George Washington’s sole contribution to the substantive debates at the convention concerned his dogged defense of the lower number on offer, and his first presidential veto concerned a congressional effort to allow half the states to go over the 30,000 number.

To Madison’s credit, he didn’t caricature the Anti-federalist position, even if he disagreed with it. In the process, however, Madison introduces into The Federalist a concept that had been for the most part lacking: the importance of virtue. I will address his arguments and counter-arguments in next week’s essay.

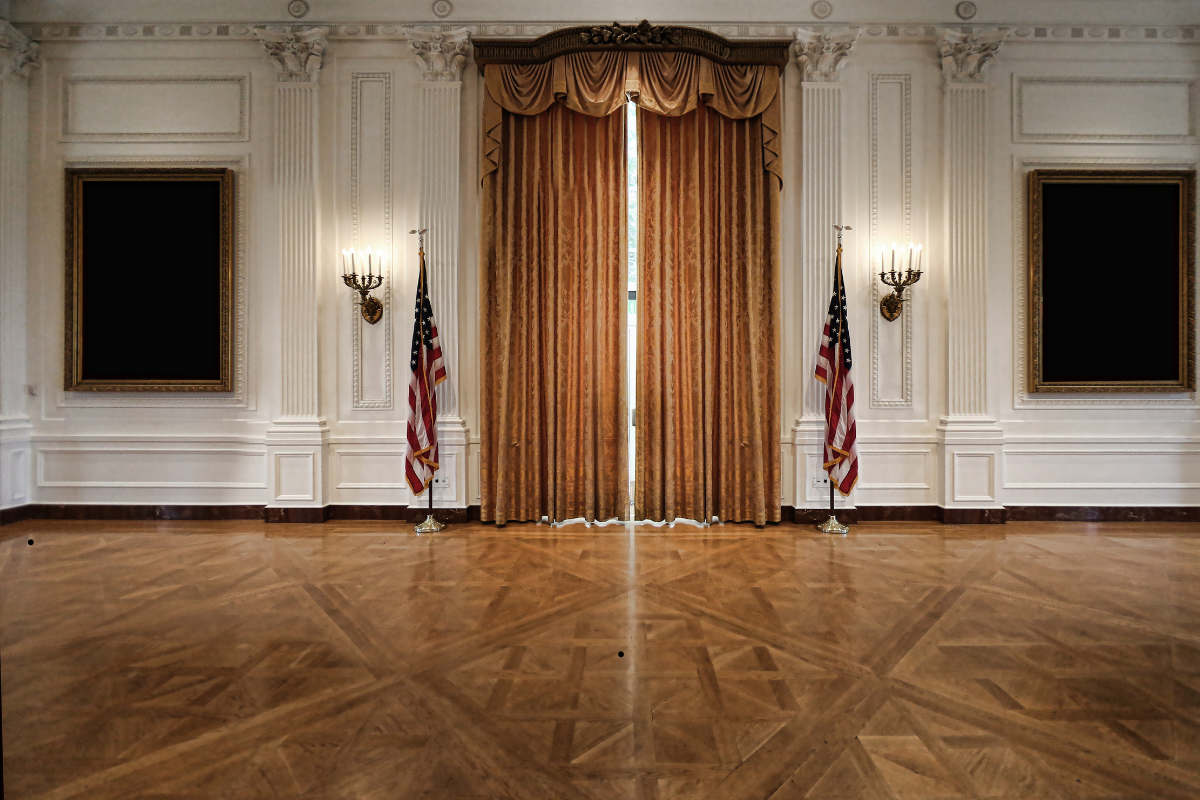

Director of the Ford Leadership Forum, Gerald R. Ford Presidential Foundation

Related Essays