Federalist 67

Twice in the last two weeks I have had to fly to our nation’s capital, desperately resisting the urge to think of it as the asylum for the ambitious and indolent that Cato predicted for it. We are all probably better off if it works well, which is different than saying if it works efficiently or powerfully. In government, less is typically more. Surely part of the problem surrounding the “shutdown” (as if!) involves a government both sclerotic and expansive, two pathologies not typically associated with good health.

I mention this because I can’t help but notice the different reactions to the shutdown based on place. I received a text from my son the other day indicating to me that he hardly noticed he didn’t have ESPN anymore as a result of the dispute between Disney and Google (which, like the Iraq-Iran war, has one wondering if there’s a way both sides can lose). I’ve talked to lots of people in America’s heartland and uniformly they have told me that the federal shutdown hasn’t made much of a difference, if any, in their lives. The main reason for this is that their livelihood doesn’t depend on the transfer of taxpayer dollars to their own wallets. When I’ve been in DC I’ve been met by panic and despair. You see, the denizens of the capitol tell me, people in the heartland just don’t get it. Why can’t they see how essential we are. And I get it: I’d hate to go more than a month without a paycheck.

I’ve said for over a month that this could drag on indefinitely because most people won’t care until it starts affecting large swaths of the population. My own guess was that canceling flights would be the mechanism that would move government to what Washington considers a compromise, which generally involves debates over exactly how much of other people’s money they’re going to spend and on what. I misspeak when I use the word “exactly” because we really don’t know how badly future interest payments will inflate the bottom line.

The Executive Branch

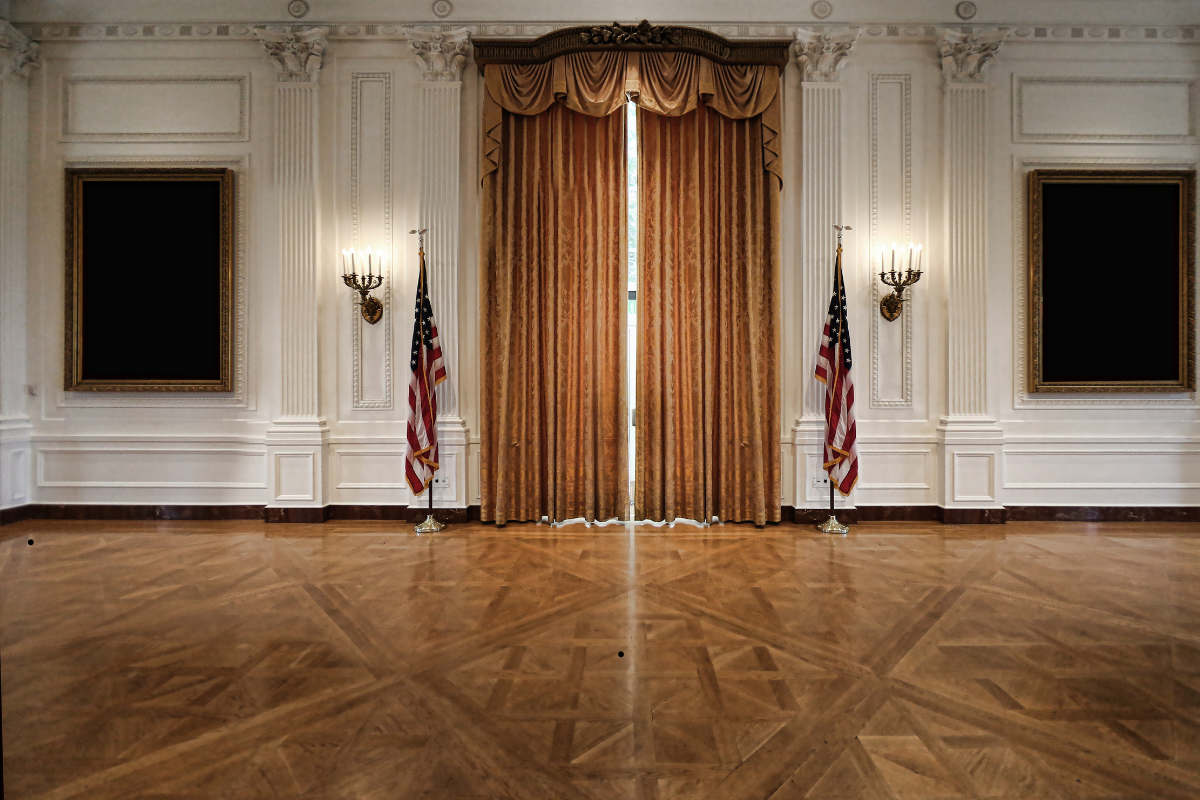

The Washington panic as opposed to midwest repose implicates debates that Hamilton begins to address in Federalist 67: what are we to make of the executive branch of government? In the background lay the British experience of the monarchy and also the hangers-on and sycophants who occupied the king’s courts. These were people who toadied to power, sought personal advancement and ways to enrich themselves, and made their living from politics — what we refer to as “court” politics. Those who favored “country” politics saw those who entered the “asylum” of the court as contributing nothing to the common weal but rather drew it down, even as courtiers covered themselves in the legitimating cloak of “public service,” thus indicating corruption all the way down.

I’ve argued that competing sides concerning ratification largely tracked court and country politics of 18th century England, with the Anti-federalists representing the country party. Not only removed from the corruption of a powerful capitol city, these citizens made the things and grew the things and built the things that made themselves and their communities self-sufficient and self-sustaining. A rising and powerful capitol city, as Tocqueville foresaw, would draw its strength by expropriating wealth and talent from the countryside, ultimately requiring its citizens to fight its wars. After all, how many of our wars have been fought defending our own turf from aggressive invaders?

Vague Powers

The creation of the executive branch with its vague powers and excessive duration in office — four-year terms with no term limits —sounded too much like the court party of 18th century England. It squinted toward monarchy, Patrick Henry observed. The Anti-federalists were the original “No More Kings” movement, not because they didn’t like a particular figure who held the office but because the office itself was too courtly and too open to abuse and sycophancy. One doesn’t get access by giving the president the business. Anti-federalists may have been content to have Washington hold that kind of power, but they also understood enough about biology and human nature to realize we would not always have Washington in the executive chair.

In his 4th and 5th letters Cato expressed his concerns about the presidency, an office both novel and all-too-familiar. The greatness of power, Cato reminded readers, should be accompanied by the brevity of its duration. Because of his appointment powers, the president would attract “expectants and courtiers,” those more interested in greatness and glory than in the simple life of virtue. In words that feel both prescient and familiar:

“The ten miles square, which is to become the seat of government, will of course be the place of residence for the president and the great officers of state—the same observation of a great man will apply to the court of a president possessing the powers of a monarch, that is observed of that of a monarch—ambition with idleness—baseness with pride—the thirst of riches without labour—aversion to truth—flattery—treason—perfidy—violation of engagements—contempt of civil duties—hope from the magistrate’s weakness; but above all, the perpetual ridicule of virtue—these, he remarks, are the characteristics by which the courts in all ages have been distinguished.”

President as Pawn

Then, too, Cato complained about the mode of election that placed an additional barrier between the people and the chief magistrate, making it more likely that he would be the pawn of vested interests than the servant of the people. The courtiers would develop manners and habits and ideas and interests contrary to those of the rest of the country. Unlike many monarchs the President would be no mere figurehead but would be endowed with actual legislative powers. The president would be able to employ troops without Congressional consent, a power the king of England would envy. The limits on presidential power were not clearly delineated, and power tended not to ratchet backward. Once a president acquired power he would seek to augment it rather than retract it. “Great power,” Cato lamented, when “connected with ambition, luxury and flattery, will as readily produce a Caesar, Caligula, Nero, and Domitian in America.” Or perhaps a combination of the worst qualities of all of them in one person.

Hamilton’s Response

Despite his declamations in Federalist 1 that republicanism required skepticism of oneself and charity toward ones opponents, Hamilton displays none of those qualities in 67. The essay deals very little with the substance of Article II, nor with Anti-federalist arguments against it, but instead offers a series of pearl-clutching hysterics. Instead, he accused the Anti-federalists of a “talent of misrepresentation,” drawing their arguments “from the region of fiction.” According to Hamilton, the fevered imaginations of the Anti-federalists led them to see the President thusly:

“He has been decorated with attributes superior in dignity and splendor to those of a king of Great Britain. He has been shown to us with the diadem sparkling on his brow and the imperial purple flowing in his train. He has been seated on a throne surrounded with minions and mistresses, giving audience to the envoys of foreign potentates, in all the supercilious pomp of majesty. The images of Asiatic despotism and voluptuousness have scarcely been wanting to crown the exaggerated scene. We have been taught to tremble at the terrific visages of murdering janizaries, and to blush at the unveiled mysteries of a future seraglio.”

One would search in vain for descriptions of that nature by any Anti-federalist writer; they simply drew attention to the fact there was something deeply anti-democratic about the office itself and that it was the embryo of monarchy.

Hamilton, undeterred, characterized Anti-Federalist arguments as lacking in “seriousness” and “not less weak than wicked,” designed “to pervert the public opinion” motivated by “the unjustifiable licenses of party artifice.” Giving up any pretense of fair-mindedness, Hamilton bellowed that “It is impossible not to bestow the imputation of deliberate imposture and deception upon the gross pretense of a similitude between a king of Great Britain and a magistrate of the character marked out for that of the President of the United States. It is still more impossible to withhold that imputation from the rash and barefaced expedients which have been employed to give success to the attempted imposition.“

The Tone of the Essay

Whew. Hamilton spends the bulk of 67 engaged in such invectives, surely a record for any of the Federalist essays. He did engage one substantive complaint about the president’s power to fill vacancies in the Senate and noted that most governors enjoyed an analogous power; but he proceeds to treat this minor complaint as if it discredits all complaints. If the Anti-federalists willfully misconstrued that power, he argued, how could you trust any complaint they have? Such bad faith “must have originated in an intention to deceive the people, too palpable to be obscured by sophistry, too atrocious to be palliated by hypocrisy.”

Resorting once again to his “fair and impartial judgment” of the matters at hand, Hamilton tried to convince readers that his characterizations were completely fair as well. Far be it from him to overstate the opposition argument. Indeed, he claimed that his credibility and fair-mindedness had already been established in prior essays. “Nor have I scrupled,” he wrote, ‘in so flagrant a case, to allow myself a severity of animadversion little congenial with the general spirit of these papers.”

I think 67 occupies a rather unique place in the whole set of essays. Hamilton makes little effort here to deal with substantive issue and specific powers. Rather, a vitriolic energy was poured into defending the very idea of the office, indicating Hamilton’s deep commitment to a powerful executive as the linchpin of his constitutional system. Such passion would do little to allay Anti-federalist worries that Hamilton himself and the office he so vigorously defended was anything less a monarchical fly in the democratic ointment.

Director of the Ford Leadership Forum, Gerald R. Ford Presidential Foundation

Related Essays