Civil Rights Cases (1883)

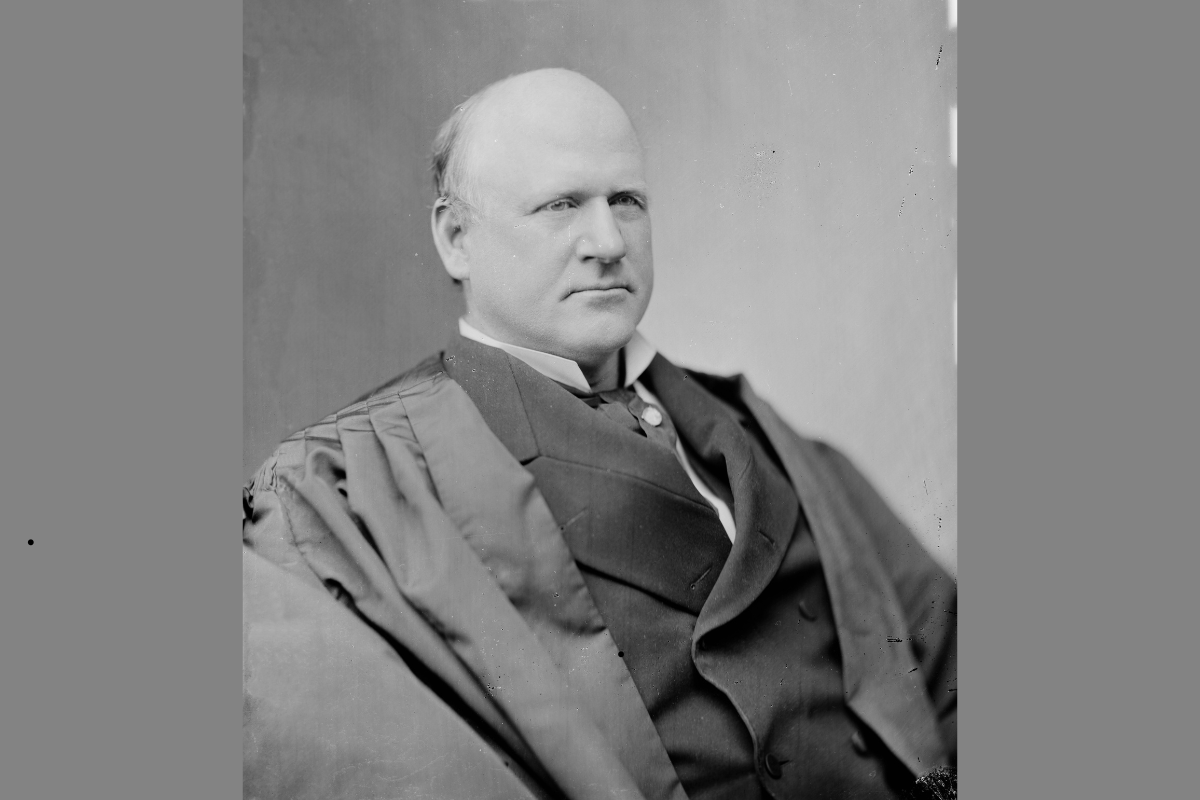

John Marshall Harlan became known as the "Great Dissenter" for his fiery dissent in Civil Rights Cases and other early civil rights cases.

Introduction

The post-Civil War Reconstruction Amendments have been described as a second framing of the Constitution. Such was the enormity of the expansion of rights and liberties that would come via the due process and equal protection clauses of the 14th Amendment. Yet it would take close to a century to begin to truly realize the primary animating aim that drove the passage of those amendments – namely, the extension of broad-based equality to freemen and Black citizens. Instead, the unfortunately titled Civil Rights Cases demonstrated how a High Court manned by justices with little or no regard for the plight of former slaves could redirect the Constitution away from, and sometimes in direct contradiction to, the original purposes of the 13th-15th amendments.

Reconstruction and the Futility of Legislative Efforts to Protect Freemen’s Civil Rights

Between 1865 and 1870, the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments (referred to as the Reconstruction Amendments) were passed, each including a clause empowering Congress to enforce it through appropriate legislation. With high rates of Black voting in the south and a significant Black legislative presence, the Ku Klux Klan formed in 1866, growing rapidly and quickly turning into a force for widespread violence across the south. Congress responded with a handful of Enforcement Acts that were aimed at protecting Black voting and other civil rights, and criminalizing the work of the Klan. But the Supreme Court would prove instrumental in neutering these statutes and translating Congressional will into impotence.

This was due in no small part to the outsized influence of President Grant in shaping the Court, with four appointments in a matter of several years. To a man, the appointees were corporate lawyers mostly preoccupied with matters of business whose general posture toward the plight of former slaves ranged from disinterest to outright animus. Indeed, the string of picks to the Supreme Court in the two decades from the Civil War into the 1880s revealed a Republican Party whose anti-slavery bona fides did not extend to the judiciary. From 1862 to 1882, five Republican presidents appointed (and had confirmed) some fourteen justices to the Supreme Court. With the exception of Justice Harlan, who would come to be known as the Great Dissenter, it would prove nigh unto impossible to locate another justice who exhibited any sympathy, let alone enthusiasm, for the constitutional claims of former slaves.

With the death of Salmon Chase in 1873, the Court lost it most vigorous crusader for racial equality. Chase’s death gave President Grant his fourth and final judicial appointment just in time to decide U.S. v. Cruickshank (1876), a case which would send a foreboding message to the future of federal protection for the rights of freemen. The appointment proved an ordeal, with the first six men to whom Grant offered the seat declining or withdrawing in the face of Senate opposition. Finally, Grant managed to push through a lackluster Morrison Waite, who was Chase’s opposite in every way, including in his disdain for Black civil rights. The Cruickshank case grew out of the 1873 Colfax massacre, which was the bloodiest single instance of racial violence during the entire Reconstruction Era. The sordid incident involved a local political conflict over control of the local courthouse, which ended with a group of armed white men killing more than a hundred Black men, some apparently while they waved a white flag in surrender. In the absence of any local response, federal officials stepped in, indicting 97 white men, nine of whom were eventually tried under the 1870 Enforcement Act, a law passed to curb Klan violence against Blacks. Two of the nine were convicted for depriving two Black men of their enjoyment of their civil rights (they were murdered in the massacre). The defendants appealed to the Supreme Court, which overturned their convictions and ruled that the Act applied only to actions of the state and not to those committed by individuals or as a part of private conspiracies. Chief Justice Waite construed the 14th Amendment as only prohibiting “a State from depriving any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law. . . but [adding] nothing to the rights of one citizen as against another." That not a single justice opposed the dismissal of the indictments made clear the direction of the Court.

By the time the Civil Rights Act of 1875 was passed, Reconstruction was on its last legs; enthusiasm was waning in the North and spreading violence in the South effectively suppressed the votes of Blacks and southern white Republicans. The Civil Rights Act was the final gasp of Reconstruction, passed by a lame duck Congress after the elections gave a clear congressional majority to anti-Reconstruction forces. The Act outlawed racial discrimination in most public places, stating that “All persons within the jurisdiction of the United States shall be entitled to the full and equal enjoyment of the accommodations” of restaurants, theaters, hotels, railroads, and “other places of public amusement . . . and applicable alike to citizens of every race and color.”

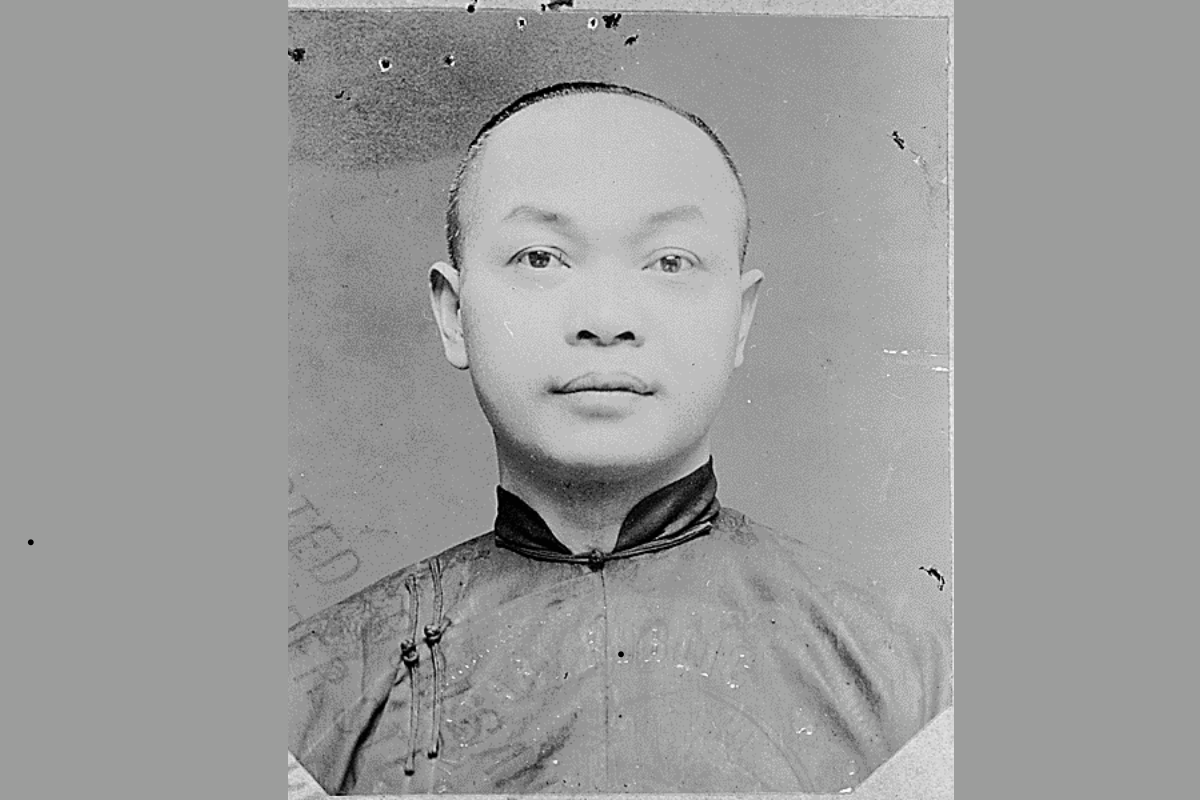

The Civil Rights Cases of 1883 marked the death knell of the Civil Rights Act of 1875, and with it the hope of federal legislative enforcement of the Reconstruction amendments. The proceedings before the Supreme Court were straightforward, involving a handful of cases that originated in Kansas, California, Tennessee, and Missouri, and were consolidated for hearing before the Court. The cases included claims raised by black citizens alleging that their rights to peaceably enjoy and participate in a variety of activities had been denied in the contexts, respectively, of dining at a restaurant, attending an orchestra concert at the theatre, riding a railway car, and securing lodging at a hotel. In each instance, the business owners contended that the Civil Rights Act unconstitutionally encroached upon their property rights to run their establishments as they desired.

The Majority Opinion

Justice Joseph Bradley, who had cast the deciding vote for the panel that put Rutherford Hayes in the White House in the contested presidential election of 1876, wrote for an 8-1 majority striking down the Civil Rights legislation as an unconstitutional exercise of Congress’s authority under the 13th and 14th amendments. In rejecting the 13th Amendment as a basis for the statute, Bradley found that the amendment was only intended to address the institution of “slavery and its incidents.” He rhetorically asked whether the denial of the accommodations sought by the plaintiffs amounted to “any manner of servitude, or form of slavery, as those terms [we]re understood in this country.” Bradley had no problem deciding that they did not. The 13th Amendment had no relation to race but only to slavery, strictly defined and narrowly understood. Bradley reasoned that “It would be running the slavery argument into the ground to make it apply to every act of discrimination which a person may see fit to make as to guests he will entertain, or as to the people he will take into his coach or cab or car; or admit to his concert or theater, or deal with in other matters of intercourse or business…”

In resolving the question, Bradley conveniently overlooked the fact that the congressional backers of the bill had in fact employed the very same word in their discussion of the proposed legislation, considering as “incidents to slavery” those practices and laws designed to keep blacks in subjugation to whites. It would hardly have been a stretch to find that racial discrimination in barring plaintiffs from those activities and accommodations they sought to enjoy could easily have fallen within the ambit of “incidents.”

Bradley did acknowledge that the 14th Amendment, in fact, extended the equal protection of the laws to identifiable races and classes of people. But that protection only extended to official state action that denied freemen equal protection of the law. He queried whether “the act of a mere individual, the owner of the inn, the public conveyance or place of amusement” could be regulated by Congress without “the denial of the right [having] some State sanction or authority.” For Bradley, the answer was clear; the 14th Amendment provided no basis for reaching such discrimination. The Constitution did not “authorize Congress to create a code of municipal law for the regulation of private rights; but to provide modes of redress against the operation of state laws . . .” Bradley piously lectured the plaintiffs that “there must be some stage in the progress of [a former slave’s] elevation when he takes the rank of a mere citizen, and ceases to be a special favorite of the laws, and when his rights as a citizen, or a man, are to be protected in the ordinary modes by which other men’s rights are protected.”

The Great Dissenter Speaks

Only Justice John Marshall Harlan took issue with Bradley’s decision. In a lengthy dissent, Harlan determined that Congress had meant to eliminate all discrimination against former slaves and to ensure their enjoyment of “rights belonging to them as freemen and citizens; nothing more.” In his view, the majority opinion gutted the “substance and spirit” of the Civil War amendments. The enforcement provisions were intended to permit Congress to directly prohibit all race-based discrimination by states and individuals. He found the distinction between state action and private behavior “entirely too narrow and artificial,” arguing that “[i]n every material sense applicable to the practical enforcement of the Fourteenth Amendment, railroad corporations, keepers of inns, and managers of places of public amusement are agents or instrumentalities of the State, because they are charged with duties to the public, and are amenable, in respect of their duties and functions to governmental regulation.” He invoked a familiar common law axiom that “when private property is devoted to a public use, it is subject to public regulation.” If owners of public accommodations were obligated to serve “all unobjectionable persons who in good faith apply for them,” as Bradley had conceded, how could they deny service based upon race? Harlan concluded by declaring that “no state, nor the officers of any state, nor any corporation or individual wielding power under state authority for the public benefit or the public convenience, can, consistently either with the freedom established by the fundamental law, or with that equality of civil rights which now belongs to every citizen, discriminate against freemen or citizens, in their civil rights, because of their race, or because they once labored under disabilities imposed upon them as a race.”

Beyond the moral clarity of his dissent, Harlan anticipated arguments far into the future that would eventually provide the basis for upholding federal civil rights legislation. He enquired whether “Congress, in the exercise of its power to regulate commerce amongst the several states” could outlaw discrimination in public services or goods passing from one State to another. This would come to pass eighty years later, when the Warren Court upheld the Civil Rights Act of 1964 as applied to a segregationist motel owner whose establishment was likely to attract guests from another state, and hence was subject to Congress’s power to regulate interstate commerce.

Consequences

The public reception to the Civil Rights Cases was mixed, with initial reaction falling along predictable racial lines. Most establishment voices, including some of the most august journalistic outlets, lauded the majority opinion as a sensible rejoinder to what many considered to be misguided legislation seeking to impose social equality rather than advance legal rights. Direct criticism of the case in the press was relatively rare.

In contrast, black leaders and their white allies were devastated, rightly reading the decision as the demise of the cause of public rights for former slaves. Within a week, a mass protest took place in Washington D.C., with Frederick Douglass as the prime speaker. He indicted the Court for ignoring the true spirit and intent of the amendments.

Liberty has supplanted slavery, but I fear it has not supplanted the spirit or power of slavery. Where slavery was strong, liberty is now weak. . . O for a Supreme Court of the United States which shall be as true to the claims of humanity as the Supreme Court formerly was to the demands of slavery! When that day comes, as come it will, a Civil Rights Bill will not be declared unconstitutional and void, in utter and flagrant disregard of the objects and intentions of the National legislature by which it was enacted, and of the rights plainly secured by the Constitution. . . This decision. . . admits that a State shall not abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States, but commits the seeming absurdity of allowing the people of a State to do what it prohibits the State itself from doing.

Similar meetings in cities throughout the north echoed Douglass. Critics did not limit their politicking to mere rhetoric or protest, however. While the decision sharply circumscribed the reach of federal civil rights protections, activists exploited Chief Justice Waite’s admission that those injured by private acts of discrimination could “presumably be vindicated by resort to the laws of the State for redress.” In other words, the Constitution allowed states to do what it said Congress could not, namely protect against private acts of racial discrimination. The concession provided a path for proponents of racial equality to pursue limited state-level protections in the years following the decision. The result was a wave of state-level legislative action advancing racial equality in public accommodations. At least ten northern states in the 1884-85 legislative cycle passed such laws, using the federal Civil Rights Act of 1875 as their template.

Yet those laws were no substitute for an encompassing federal civil rights agenda. Without the equivalent in the south of the leverage black activists and white civil rights proponents wielded in the north, the success of state-level action was geographically limited. Instead, precisely the opposite occurred. The Civil Rights Cases opened the door to the codification by southern states of what had theretofore been mere practice of private racial discrimination. The pervasive enactment of Jim Crow laws legalized the treatment of backs as second-class citizens. The bookend to Plessy v. Ferguson a decade later, the Civil Rights Cases laid the foundation for segregation of blacks in housing, education, work, and virtually all facets of public life. The confinement to a status of second-class citizens would stand for close to a century. Only in Heart of Atlanta Motel v. U.S. (1964) did the Warren Court finally affirm Congress’s reliance on the commerce clause to pass the historic Civil Rights Act barring racial discrimination across a wide range of public accommodations.

A Postscript

The Civil Rights Cases marked a coming out of sorts for Associate Justice John Marshall Harlan, whose dissent demonstrated that one need not be captive to one’s personal experience or the cultural morays of the time. Born into a prominent, slave-owning Kentucky family, Harlan himself owned a handful of slaves who would not be freed until the passage of the 13th Amendment required it. One would hardly have expected Harlan to become the judicial paragon of racial equality; his political stances had included opposition to Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation and ratification of the 13th amendment, which he viewed as a “flagrant invasion of the right of self-government.” He initially resisted the Reconstruction policies of the Republican party and saw the Civil Rights Act of 1875 as federal overreach. Over time, however, he manifested a remarkable prescience and ability to chart where the Court’s jurisprudence might eventually go on important questions. Better known for his celebrated dissent in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), the Civil Rights Cases was Harlan’s first significant break with the Court. The Great Dissenter would later lodge his disapproval of the Court’s undercutting of anti-trust law in U.S. v. E.C. Knight (1895) and oppose its embrace of economic substantive due process in Lochner v. New York (1905). He also was the first to posit that the Bill of Rights applied to the states by incorporation via the 14th Amendment due process clause.

A rich irony in Harlan’s story is that his elevation to the Court came as a political reward for his tireless efforts in swinging his home state of Kentucky’s delegates behind Rutherford Hayes at the Republican presidential convention of 1876; as part of the machinations surrounding the controversial general election, Hayes signaled his amenability to removing federal troops from the south, thus ending Reconstruction for good and opening the door to Jim Crow policies, the opposition to which would burnish Harlan’s historical reputation. Harlan would serve until his death in 1911, a tenure of 33 years that at the time was the third longest in the Court’s history.