Federalist 49

Historians have long contrasted Hamilton’s vision of America with that of Thomas Jefferson: one aristocratic and the other democratic; one with an energetic national government and the other decentralized with an emphasis on individual rights; one with a loose construction of the constitution and the other strict; one with rule by elites and the other populist in tone; one focused on manufacturing and trade and the other agrarian. Henry Cabot Lodge had already in 1902 suggested that the trajectory of American history was the battle between these two approaches. The writer Claude Bowers went as far as to say that “the struggle of these two giants surpasses in importance any other waged in America because it related to elemental differences that reach back into the ages, and will continue to divide mankind far into the future.” Between these two seminal figures in American party politics stood Jefferson’s fellow Virginian James Madison, temporarily an ally of Hamilton’s but soon to return to Jefferson’s side.

Madison quoted Jefferson liberally, although not by name, in both Federalist 48 and 49. Jefferson believed that (in his own words) “Our peculiar security is in possession of a written Constitution,” one that clearly defined and limited the powers of government. As I argued in my last essay, Madison expressed in 48 his reservation that a written Constitution was anything more than a mere parchment barrier, that simply the act of writing something down would not be sufficient to restrain the designs of ambitious men, especially since they would interpret those words to mean anything they wanted. If putting those limits in writing proved inadequate to the task of keeping government properly restrained, what would?

How Jefferson Wanted to Keep Government in Check

Jefferson had made his view clear: since government itself was a creation of the people, and all sovereignty ultimately resided in the people, the people should have recourse to reconstructing any government that no longer served their purposes appropriately. The people -- “the only safeguard of the public liberty” -- alone should judge when constitutional limits had been transgressed, meaning that Americans should be willing to reconvene for the purpose of writing new constitutions. Notorious for his never-ending enthusiasm for the French Revolution, author of the apothegm that “a little revolution now and then is a good thing, and as necessary in the political world as storms in the natural,” Jefferson argued that extending the preamble’s promises to posterity amounted to a kind of enslaving of one’s descendants. Constitutions should be reconstructed every generation, for even if the people could be temporarily led astray, they would always correct themselves and their deposits of wisdom would always prevail.

In 49, Madison engaged Jefferson’s argument about referring constitutional disputes back to “the people.” Acknowledging that Jefferson’s plan displayed “a turn of thinking original, comprehensive, and accurate,” and that it seemed “strictly consonant to the republican theory,” and conceding that “a constitutional road to the decision of the people ought to be marked out and kept open,” Madison nonetheless would reserve use of that path only for “certain great and extraordinary occasions.”

Madison’s Criticism of Jefferson

Political thinkers like to distinguish between ordinary politics and the politics that occurs in extreme circumstances. The former can operate within firm limits and moral compass while the latter may call for measures that would be considered extreme or dangerous in normal times. Madison believed that Jefferson was confounding the two, that the national government could operate ordinarily without having to resort to extreme measures. Granted, there might be a time and a circumstance under which a new Constitution might prove necessary, but Madison was wary of the way Jefferson folded those conditions into the ordinary course of events.

Keep in mind that Madison was dealing in these five papers not with the relationship between the national government and the states, but between the three branches of the federal government. Should one of the branches of government, or a combination of two of them, usurp the prerogatives of one or two of the other branches, a constitutional convention would not only prove an extreme response – the proverbial killing of a fly with a hammer -- but a pointless one as well. It would fail to fix the immediate problem, instead substituting a new of set of problems in its place.

When Jefferson imagined a constitution that did not bind generations, he did so by imagining a world where older generations all died on the same day and new ones were all born on the same day. This thought experiment provided him with a way of justifying intergenerational discontinuity but bore little resemblance to the way people actually live. Madison detected that the end result – repeated conventions – would be so destabilizing as to make governing impossible (which may well have been Jefferson’s goal). “Frequent appeals” to the people, Madison worried, would “deprive the government of that veneration which time bestows on everything.” If reason alone ruled the world, then Jefferson’s confidence in the people reconstituting government might be justified; “but a nation of philosophers,” Madison observed, was “as little to be expected, as the philosophical race of kings wished for by Plato.”

What Role for “The People”?

The differing levels of confidence Jefferson and Madison placed in “the people” resulted from competing understandings of human nature itself. Jefferson tended to believe in the natural goodness of people and that they could be counted on to be rational; in those instances where rationality proved undeveloped, a system of public education could step into the breach. Madison had a more skeptical view: granted, human beings were capable of doing good things, but they were likely to be selfish and full of vice. In any case, you could count on their viciousness in a way you couldn’t depend on their virtue – especially in the extreme case.

Nor did Madison share Jefferson’s confidence in human rationality. Passion, not reason, was in the driver’s seat (Madison shared Hume’s view that “reason is and ought always to be the slave of the passions” — although he may quibbled about that “ought”), and repeated constitutional conventions would not replicate the singularly cool deliberation that occurred in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787; rather these conventions would stoke “the public passions,” and “the passions, therefore, not the reason, of the public, would sit in judgment.” Reason might be the means by which the public could control government, but the purpose of government was to control the passions.

Nor had Jefferson accounted for one thing Madison and many other framers feared: the possible emergence of political parties. In Federalist 10 Madison noted the persistent presence of “passion and interest” in politics, accommodating those impulses rather than repressing them. What Madison was not yet familiar with – nor could he be, given that the creation of the idea was still thirty years off – was the reality of an ideological party. In 49 he did express concern about parties, but he connected those to a specific set of interests, in this case the interests that result directly from the delegations of power. In other words, government would have to negotiate legislative, executive, and judicial interests, or parties, and this negotiation would prove difficult because there was no neutral party to either review or adjudicate the inevitable disputes.

In What Sense Do The People Rule?

Jefferson believed he had solved that problem by referring to the people as the sole adjudicators in such conflicts, they being left free to adjust the balances of power as they saw fit through frequent constitutional reform. Unlike Jefferson, who believed in the constancy and reliability of public sentiment, Madison thought the people would also be riven by party strife, gaming the reform process to advance particular interests and driven too much by passion and too little by reason. The solution, he believed, had to reside within the interactions of the three branches rather than by reference to an external authority. Not even a written constitution would do.

While Madison did acknowledge that appeals to the people would be the ultimate check on the abuse of power, he believed elections rather than conventions had to be the primary mechanism. Because of the manner by which they attained office, the executive and judicial branches would be at a disadvantage, judges being “too far removed from the people” and executives “always liable to discoloured and rendered unpopular.” Those two branches would have the most cause for appeals of relief from an imperious legislature, but also would be least successful.

Members of the legislature, Madison reminded readers, “are distributed and dwell among the people at large” and are abound to the people “by connexions of blood, of friendship, and of acquaintance.” On the one hand these connections would insulate the legislative body from complaints arising from the other two branches, while on the other hand, Madison cleverly argued, those connections would render Jefferson’s conventions pointless because the delegates would be “composed chiefly of men who had been, or actually were, or who were expected to be members of the [legislative] department whose conduct was arraigned. They would consequently be parties to the very question to be decided by them.”

“No man can be a judge in his own case” is a fundamental premise of liberal politics. Jefferson’s convention would fail to maintain order because they would inevitably devolve to the interests of the popular branch of government, and Publius’ sound republican system required a checking on these popular impulses. This reformulation of Aristotle’s model for good government – a mixed regime, where aristocratic, monarchical, and democratic elements combined into the sturdiest possible structure – would also prove vulnerable to drift. Time has not been kind to Madison’s assumptions concerning an imperial legislature, and the absence of any outside bar designed to restrain the growth of government beyond its constitutional bonds has proved to be a problem.

Between Madison’s confidence and Jefferson’s doubts that the branches would constantly check one another rested the liberties of the people. Frequent conventions having been dismissed, elections alone could serve as the final palladium of their liberties, but only if people would zealously and diligently attend to all threats. The Anti-federalists may have had more confidence in the people, but they also knew that designing men could use power to buy the people off with free lunches and other handouts until we became servile, our taxes going to a government that would give us only a portion of our contributions in return. Undoubtedly, this is why Jefferson thought a little revolution now and then would be a good thing — the tree of liberty, after all, being nourished by the blood of patriots.

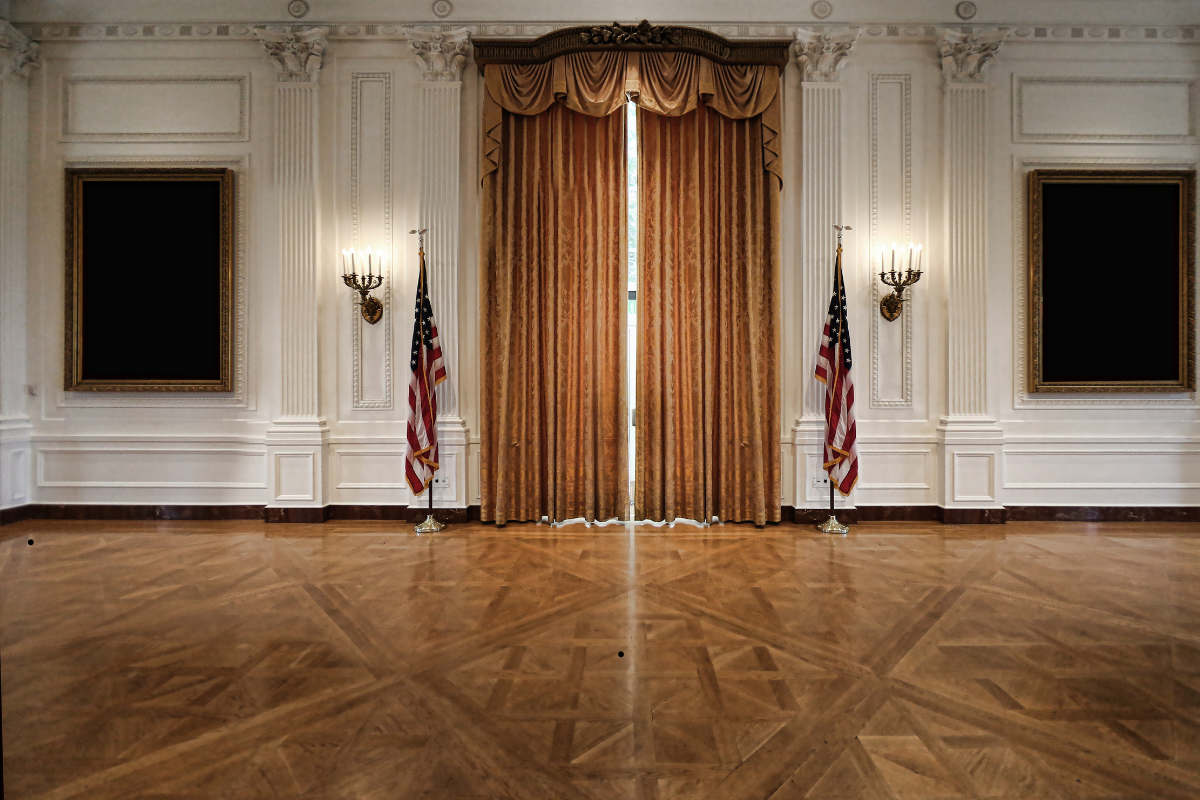

Director of the Ford Leadership Forum, Gerald R. Ford Presidential Foundation

Related Essays