Federalist 50

A political regime has constituent parts: a principle of rule; territorial sovereignty; members of the community; a sense that the polity in some ways represents the order of the cosmos itself; organized authority. To change a political regime you can change it demographically (who counts as a citizen), geographically (territorial expansion or contraction), culturally (including its animating purposes), or its basic rule of law. Publius believed that while America had the capacity to change territorially it would remain demographically and culturally fairly homogenous. Granted, there would be distinctions, but those would occur within a largely shared cultural universe.

Given Anti-federalist worries about the consolidation of power in a central government, Publius knew that ratification hinged on the principle of rule. Knowing that the Constitution’s fate rested on the ability to contain the greater energy for which the author’s advocated, Publius focused on arguments concerning the guardrails placed around governmental power, and for Madison this meant mainly legislative power. In 49 Madison engaged Jefferson’s argument that since the people were the source of all authority they retained to themselves the right to alter or even abolish the government should it expand beyond its bounds. Madison regarded this as fundamentally true but practically irrelevant.

As I demonstrated last essay, Jefferson went further than this. He argued that writing new constitutions should be a permanent feature of American political life, in no small part because one generation should not impose itself on the next. No doubt, in the end the people are the final palladium of liberty, just as there is little doubt, as Tocqueville argued, that a government always reflects the sentiments and desires of (alas) a simple majority of the people. Nor can a government long last when it has lost all popular support. If people are dissatisfied with their leaders they might take such dissatisfaction as an invitation to introspection.

Madison’s Argument Against Frequent Conventions

Madison, I argued, rejected the idea of repeated plebiscites concerning the fundamentals of political order. While acknowledging the rightness of popular sovereignty, he also worried that such reevaluations would, first of all, occur primarily in moments of crisis, when good decisions seldom get made, and, second of all, unleash destructive and self-interested passions rather than rein them in. Lincoln would later opine that constitutionalism predicated itself on “cold, calculating reason,” a view not too far from Madison’s own. Passions always required restraint, but reason would allow you to take your hands off the reins. Or, to use Plato’s metaphor, the passions were like two spirited horses pulling a chariot, and the good horseman had his hands on the reins, which were, analogously, the means by which reason guided the passions (a view contrary to that articulated by the currently well-regarded Jonathan Haidt, who argues that the passions drive reason, which merely rationalizes desire).

How to fix breakdowns in the constitutional order? Logically speaking, the differing responses result from how significant the breakdown is. Jefferson, always an apologist for 1789 and author of the American Declaration of Independence, assumed that revolution was not only a legitimate response but one that could and should be exercised with some regularity. When people wearied of the gradually increasing weight of the yoke of oppression, there would be only one way to throw it off. Madison conceded the measure in the extreme case, but also expressed worry that Jefferson would man the barricades too quickly (or, more accurately in Jefferson’s case, would ask someone else to man them).

Publius had enough confidence in the overall design to defer such measures. Granted, violations would occur, but would seldom be so extreme as to justify measures equally so. While not yet addressing the amendment process, clearly this would be the preferred means by which readjustments could best be made. Madison clearly believed, at this point at least, that the carefully calibrated mechanisms of government worked in coordination well enough that only fine tuning would be required, and such recalibration would prove a relatively simple operation.

Furthermore: what would failure of the Constitutional design actually look like? Again, one can imagine all sorts of possibilities here, some of them realized in the American civil war. Publius may have considered the collapse of legitimacy itself, but only in the abstract. It was left to the Anti-federalists to think through the sectional rivalries as well as differences in culture and political economy that would drive the wedges that would split the nation apart.

Practical Reform

Madison’s worries were more pedestrian, but still consequential: What happens when one branch (Madison assumed the legislative) became imperious in its designs and usurped the authority of the other two? Madison always reasoned with precision: any negative action had to have a negative and reciprocal reaction that was proportional to the violation itself. You didn’t respond to the possibility of legislative encroachments by getting rid of the legislature, just as you don’t abolish the pardoning power just because it gets abused. You correct the abuse, you don’t remove the power.

Instead of crisis-driven revisions, what if you reviewed and rewrote the Constitution periodically, at set intervals? Madison weighed this possibility but found it, too, wanting. For one thing, there is no secret formula for setting the interval: make it too narrow and you might be correcting problems that don’t exist and set the intervals too far apart and the poison may have fully taken over the patient by the time the revision happens. In either case, the prospect of revision was at best “a very feeble restraint on power.”

There was a more serious consideration, however: who would do the revising? Looking at Pennsylvania’s earlier experiment in mandatory constitutional revision Madison concluded that its failure resulted from the fact that the persons doing the revising were the same persons responsible for the violations in the first place, namely, the elected representatives.

The Problem of Political Parties

None of that is what makes Federalist 50 particularly worth our attention. It is one of the shorter essays, but also one where Madison addressed one of the most serious issues in any democratic republic: the existence of political parties. It is a truism among political scientists that the framers of our Constitution feared the emergence of political parties and their capacity to rupture the polity. Granted, the Constitution makes no mention of political parties, so they are extra-constitutional features that have to be adapted to the structure. This thumbnail reading of history wherein the framers feared the emergence of parties but had to adapt by the contentious election of 1800 is both widely repeated and patently wrong.

This whole series of essays revolves around deep divisions reflected already in the Constitutional Convention itself as well as the ratification debates. America was already deeply divided over issues of good governance and its purposes, over the nature of liberty, over the emergence of serious war powers, and while citizens may have not been formally organized into parties in the ways we understand them, where their central purpose is staffing offices through nominating and electing, parties already made their presence felt in determining who attended conventions.

Madison saw this at work in the Pennsylvania case. The efforts at constitutional revision there failed largely because the delegates “had also been active and leading characters in the parties which pre-existed in the state.” As a result, “[t]hroughout the continuance of the council, it was split into two fixed and violent parties” [emphasis added]. Progress stalled when delegates took predicatable positions that reflected competing interests. Standing outside the debate (would that modern Americans had this capacity!) Madison saw that the spirit of partisan interest infected both sides equally. It was “passion, not reason” that “presided over their decisions” [Madison’s emphasis]. Reason presents a fulsome range of opinions that leads to sound conclusions while passion flattens everything, creating a siloing effect. Because of its tribal effects, passion makes negotiation difficult at best, impossible at worst.

When men exercise their reason coolly and freely on a variety of distinct questions, they inevitably fall into different opinions on some of them. When they are governed by a common passion, their opinions, if they are so called, will be the same.

Pennsylvania’s experiment in creating a “censorial body” that would correct imbalances in the state’s constitutional order proved worse than ineffective, for they partook of the very poison they sought to purge. Here, I think, is one of Madison’s most important lessons, one we would do well to remember today, and is also a reminder of why getting our history right matters. The founding myth — that the framers feared the rise of political parties and sought to avoid them — makes it seem as if our current divisiveness is somehow sui generis and also our distinctive pathology. Again: nonsense. Americans have always been divided, and as I argued in my reflections on Federalist 10, attempting to get rid of those divisions would require either the elimination of liberty or the changing of human nature itself, the effort at the latter always resulting in the killing of the former.

Dealing with Parties

We must instead understand how we can create a political system that channels those instincts, and hopefully in such a way that this channeling is productive of the common good. This idea is central to Madison’s thoughts on constitutional design. Ever the realist on this point, Madison saw how partisan divisions would always threaten to rend the fabric of constitutional order, so rather than not accounting for them and letting them tear the thing apart, better to place a pair of scissors in their hands that would allow for a careful and productive cutting.

Madison warned against the tendency to think that crises resulted from extreme partisanship that thus required dramatic interventions. Reflecting on the extant “narrative” (oh cursed word!) that Pennsylvania’s crisis resulted from the fact that the state “had been for a long time before, violently heated and distracted by the rage of party,” Madison reminded readers that any viable system had to think of itself as always in this state of crisis.

Is it to be presumed that at any other septennial epoch, the same state [PA] will be free from parties? Is it to be presumed that any other state, at the same time, or any other given period, will be exempt from them? Such an event ought to be neither presumed nor desired; because an extinction of parties implies either a universal alarm for the public safety, or an absolute extinction of liberty.

It would be impossible to find persons not motivated by such factional concerns, so better to account for parties than fret about their existence.

Here, too, is one of the main lessons for today. Madison thought it neither wise nor possible to eliminate the spirit of partisanship, nor did he think the sacrifice of liberty justified the measures of order required. How, then, should we respond to extreme partisanship? Here the benefits of limited government seemed obvious, for such limits, if properly constructed, would make it impossible for one party to impose its will on another. Or so Madison hoped. As the powers of government grow, and as constitutional and cultural barriers that would mitigate the imposition of will upon one another erode, so too will partisan competition for control of the instruments of power increase. Politics becomes not only a game of brinksmanship but also revenge, the party in power extracting its pound of flesh for what the other party did when it was in power. The politics of revenge ratchets both the partisanship and the growth in power in one direction only.

This cycle of imposing one’s will and then dealing with the consequences of revenge has now become a defining feature of our politics. How did we get here? Surely Madison was right that any sensible, historically-informed idea of republicanism would have to account for partisan passions that admitted of no purging from the system; at the same time, might those impulses be, if not disciplined, at least properly leashed?

These reflections on partisanship in 50 form an important background to Madison’s extended reflection on constitutional order in 51, to which I next turn my attention. Given the central importance of Federalist 51 both in the work as a whole and in the public imagination (it is the most reproduced of the essays) I will cover it in two parts.

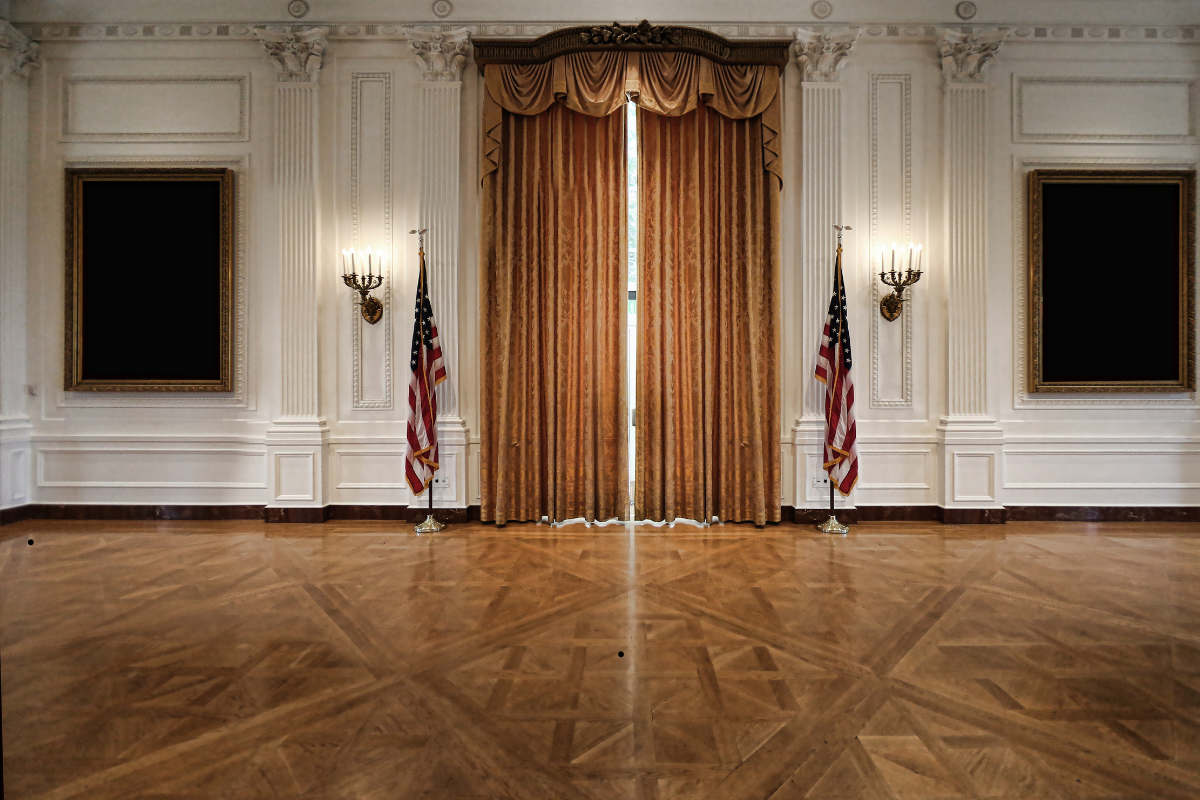

Director of the Ford Leadership Forum, Gerald R. Ford Presidential Foundation

Related Essays